This short article is here to get you grounded in using the Apache HTTP server in its particular implementation on IBM i and give you a bit of background and wisdom on that implementation.

Editor's Note: This article is excerpted from chapter 11 of Open Source Starter Guide for IBM i Developers, by Pete Helgren.

We’ll also look at Tomcat, which is an application server that is written in Java and runs very nicely, thank you, on IBM i. I also thought about writing a chapter on Java for IBM developers. I decided against doing that, though, because there is a solid book, Java for RPG Programmers (MC Press, 2006), which covers much of what I would say. That won’t stop me from talking about Java or even throwing you a Java example or two, but we won’t go quite as deep into Java as I have into other open source languages because Java has been on IBM i for, well, it seems like forever. Java also happens to easily span the IBM i, PASE, and other worlds because you can run Java natively on IBM i or in PASE. My first foray into Java was, in fact, written using SEU (I think) and compiled using CRTJVAPGM. Oh, how far we have come!

So, just to draw the distinction more clearly for you: Apache, as an HTTP server, can serve up static resources such as HTML pages and can invoke programs to create HTML using Common Gateway Interface (CGI) standard programs like PHP and CGIDEV2. It serves up HTML and other Web resources very well, but it isn’t serving up applications. In order to do that, you’ll need an application server. I am partial to Tomcat because it has been around for quite a while, but there are other Java-based application servers out there. You get a tiny scaled-down version of WebSphere with your IBM i installation, and you certainly can install the full-blown WebSphere Application Server on your IBM i, but out of the box, you get Apache and not much more.

Apache is the latest incarnation of HTTP server on IBM i. Back in the early days when websites were run by hamster wheels and hand cranks, IBM’s first foray into HTTP serving was a relatively clunky, native implementation based on the CERN HTTP server. I think this was available as far back as V3R2 and was called the “original” server when the HTTP Server (Powered by Apache) was introduced. The two servers maintained an arms-length relationship for a while, and eventually the CERN (original) implementation was retired. But, HTTP serving has been around on AS/400/iSeries/IBM i for a long time. Early on, most folks had no idea what to do with it.

Apache

What can you do with Apache? Well, since Apache is so efficient in serving up static resources and resources passed to it from CGI programs, you can leverage it for many things. I use it primarily as a reverse proxy for the plethora of programs, pages, and other plumbing in my Web apps (nice alliteration, eh?). What is a reverse proxy? A very handy little tool, in my humble opinion. If you are constrained on external IPs like I am (I get two!), then the ability to run multiple websites and yet pipe them to a single IP address is quite handy. My public-facing websites all share the same public IP, but behind the scenes, Apache directs them to their correct internal server instances—and I have a bunch of them running on my IBM i.

Here is an example of what my main Apache configuration file looks like:

As you can see, or maybe you can’t, I have several different server instances referenced here. Way at the top, the initial LoadModule directives are creating an environment where PHP apps could live, if needed. They load service programs from the ZendSvr library. I don’t have any CGIDEV2 CGI pages that live in the main configuration, but I certainly do pass the traffic back to some CGIDEV2 sites. The next thing to pay attention to is the Listen directive, which is basically saying that this server instance is running on an internal address of 10.0.10.200 on port 80, standard for HTTP.

So, you might be thinking, if this is an internal address, how does the outside traffic get in? That takes a firewall, and I have one that is out there listening with an Internet- addressable IP on port 80. The firewall then maps that traffic back to my internal address (Network Address Translation—NAT—is the process). At that point, Apache is examining headers to see which Web address is being requested, so that it can figure which host to map the traffic to internally. I skipped over all the MIME types that Apache will allow in, but those are listed (mostly video and media files)—and the first virtual host is the asaap.com site. Note that www.asaap.com will be directed to the virtual host, but also any (*) host on the asaap.com domain will also end up here (for example, mobile .asaap.com, demo.asaap.com).

Finally, we see two reverse proxy paths that point to different subdomains. This happens to be a Tomcat server instance, so the two subdomains are actually pointing to two different applications running on Tomcat. So basically, if you typed in the URL of www.asaap.com/asaap3, it would be mapped to the asaap3 application running on Tomcat on port 6080 at the internal address on 10.0.10.206.

The beauty of the reverse proxy is that you can have all sorts of servers supplying resources to the same Web domain without anyone being the wiser. So I could also have a Web server running PHP but referenced in the asaap.com URL as www.asaap.com/blog and actually have it point to a WordPress instance running elsewhere on my network. Yet even though someone navigated from www.asaap.com/asaap3 to www.asaap.com/blog, they never knew that they were changing servers. Very cool and flexible!

The other thing I have found helpful with using Apache for a reverse proxy is that by having a single “main” instance that receives all the traffic, it allows me to bounce a particular instance or change a configuration of that instance without losing all my websites. In addition, if all the servers serve sites that share the same domain, your configuration of SSL can reside on the “main” Apache instance with a wildcard certificate, encrypting all of your external traffic without the hassle of configuring SSL for every server instance you have. If you have PHP, Node.js, Tomcat, CGIDEV2, Rails, and some static resources as well, then a reverse proxy will just make life much simpler. And, in this business, simple is good!

What do CGI apps look like? Well, we can take a quick look at some CGIDEV2 configuration directives. You might see something like this:

In this case, the URL is mapping anything that follows the /mobilerem/ subdomain to the mobilerem library. So if I had a CGIDEV2 RPG program in the mobilerem library called mypgm.pgm, and the URL parsed looked like this: www.mysite.com/mobilerem/mypgm.pgm, then the directive above would execute the CGI program in the mobilerem library.

Nice and flexible!

Tomcat

Apache Tomcat has been around for years. It was one of the very first open source programs I ever installed on my iSeries. I marveled that I could “install” something on that iSeries by just unzipping a file into the IFS. Fifteen years later, nothing has changed. I can get a Tomcat server instance going in less than five minutes. Here’s how to do it.

Download Tomcat from the Apache Software Foundation website. Yes, Tomcat is an Apache product, which confuses the heck out of people because if you call it “Apache Tomcat” (which it is), they think you are talking about some derivative of the HTTP server. Nah! The Apache Software Foundation has a ton of projects, most of which go by the name “Apache (insert name here).” So, just go ahead and download the zip instance of Tomcat (or the tar..any archive) and unzip it into the IFS. I have an “Apache” folder in the root of the IFS, which currently has Tomcat 5.5.27, 6.0.33, 7.0.26, and 8.5.4 sitting in their own folders.

Once you’ve downloaded and unzipped Tomcat, you will need to make sure that the Java version you are running on your IBM i is compatible with the version of Tomcat you just downloaded. (Sorry, I guess you should have checked that first.) We’ll make a brief detour now into Java-land:

There are two main versions of IBM’s wonderful J9 JVM on IBM i: a 64-bit and a 32-bit version. Of course, you are thinking: 64 is better than 32, so let’s go with 64! Not so fast, cowboy! In many cases, the 32-bit will outperform the 64-bit version. Unless you need to use a lot of memory for your apps, start with the 32-bit JVM. If it doesn’t meet your expectations, switch to the 64-bit version. It is drop-dead simple to do so. And, don’t rely on the IBM i environment to choose your JVM version for you. You never know when some nimrod will decide to change a systemwide value that points to a different JVM, and it will break your Tomcat instance.

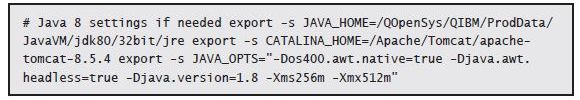

Here is what I do: after unzipping the file into the IFS, I navigate down to the /bin folder and open the catalina.sh shell script. Then I add the following lines to the script (again this is Tomcat 8 running with version 8 of the JVM):

These directives are added at the very beginning of the shell script, just after the comments about all the options in the head of the script. They have never let me down. Then I launch this guy in a CL program like so:

Couldn’t be easier.

Tomcat is an application server, so the next step is to deploy your applications by dropping the .war files (Web Archive file) into the webapps folder. They automatically deploy. You are done.

So, that is the briefest of tours in the Apache HTTP and Apache Tomcat world on IBM i. I’ll bet that most of your Web applications, whether they be PHP, Node.js, Rails, Python, RPG CGIDEV2, or even Java applications will probably sit in, or behind, the Apache HTTP server. At your service!

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online