Why are the examples for SQL always so lame? It's time to see what you can do with SQL on a real-world database.

Seriously, how often do you change the price in an entire price file by 15 percent? I don't know of a single situation in my career where that has happened. Yet that's the same lame example we see in every "SQL for business" book. Yes, SQL is great for handling sets of data, but more often than not, in the real world you have to do some analysis, some aggregation, some extraction, and then finally some manipulation. The good news is that SQL gives you lots of tools to do just that. The better news is that this article will show you some practical examples on how to use those tools.

The Wonders of Interactive SQL

Please note that this article is specifically about interactive SQL. This is in contrast to embedded SQL, in which you embed SQL statements in a high-level language program and use the SQL syntax to extend the programming language. Interactive SQL involves running individual statements by typing them directly into an interpreter of some kind.

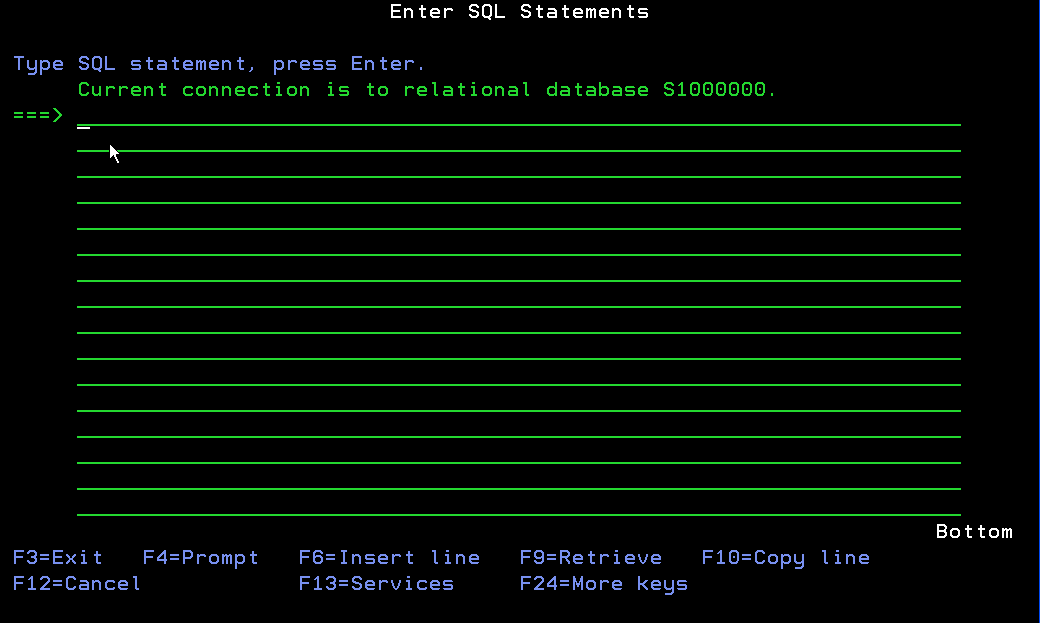

Interactive SQL in the green-screen means STRSQL. STRSQL brings up a command shell, similar to using STRQSH or to calling QP2TERM. The STRSQL shell executes interactive SQL commands directly. You can also save one or more interactive statements into a text file and run the text file using the RUNSQLSTM command, although the lack of parameters diminishes the usefulness of that technique. The STRSQL session looks like this:

Once you're in the SQL session, you can start entering commands. For example, if you wanted to update your prices by 15 percent, you could do something like this:

UPDATE PRICES SET PRICE = (PRICE * 1.15)

We know, though, that a statement like the one above isn't really very useful. The reason for this article is to provide some practical examples of SQL statements that you can use in your business.

Types of Statements

SQL is an interesting language in that it has a relatively compact syntax, at least as far as the basic instructions. In fact, for someone whose role is primarily that of data mining, the SELECT statement (in all its many variants) may be the only statement needed. Add the UPDATE statement (along with the less-used INSERT and DELETE) and most data-centric tasks are covered. However, it's the very simplicity of the language that trips up a lot of beginning programmers. While it's relatively easy to get things to happen, it's not always so easy to identify the best way to accomplish common goals. So let's address some of those, shall we?

Joining Files

One of the first non-trivial SQL concepts is that of a join. In a join, you combine columns (fields) from one table (file) with columns from another file. One of the interesting syntactical issues when dealing with SQL is the idea of "handedness." SQL distinguishes between two files by calling the first one defined the left-hand file and the second one the right-hand file. Later, we'll be talking about things like LEFT OUTER JOINs, and the idea of left and right become very important.

We can walk through a couple of simple examples. First, a one-to-one relationship, where each record in the primary or left-hand file has one record in the secondary file. A practical example might be to list items in an order but get their description from the item master file. I'll use some very simple file layouts, and even those will only be partial. For example, here's the item master, with description:

A R ITMMASR

A IMITEM 15 TEXT('Item Number')

A IMDESC 30 TEXT('Item Description')

A IMTYPE 2 TEXT('Item Type')

As you can see, I'm including very little of the file, just enough to make an example. You can see, though, that I've defined the file as an old-fashioned DDS file, complete with six-character field names, just to emphasize the point that the techniques we're talking about will work just fine with legacy databases. Next, let's take a look at the order detail file:

A R ORDDTLR

A ODORD 10S TEXT('Order Number')

A ODLINE 4S 0 TEXT('Line Number')

A ODITEM 15A TEXT('Item Number')

A ODQORD 9S 3 TEXT('Quantity Ordered')

Once again, this is a very simple example, but it's real business files with real business fields. Let's see what we can do. Well, first we can join the order lines to the item master to get the descriptions:

SELECT ODORD, ODLINE, ODITEM, IMDESC FROM

ORDDTL JOIN ITMMAS ON ODITEM = IMITEM

Like any SELECT statement, the join first specifies the fields desired, although in this case it includes fields from two files. Next, the statement identifies the two files using the JOIN ... ON syntax. The ON clause of the JOIN indicates which field (or fields) are used in each file to link the two files. One thing to note is that in this very simple example, I've been able to name the fields without having to qualify them because the field names are different in the two files. I'll show you more about qualifying field names a little later. Anyway, run this with the appropriate data and you might see a result like this:

ODORD ODLINE ODITEM IMDESC

230,045 1 ITEMA Item A

230,045 2 ITEMB Item B

230,045 3 ITEMC Item C

230,050 1 ITEMA Item A

230,050 2 ITEMC Item C

In this case, I see two orders: one with three lines, one with only two. Not only that, I see values from two different files joined by a common key field. I know that up until now this may have seemed like SQL 101. But now I'm going to go into a couple of different directions very quickly. First, let's deal with data that isn't quite as pretty as the data above.

Handling Real Data: LEFT OUTER JOIN and COALESCE

In the real world, applications sometimes use order lines to specify non-item information: things like freight charges or various adjustments to the order. Rather than create a whole different record type for this sort of line, we simply add records without an item number. But that brings up one of the vagaries of the SQL syntax. If the item number from the ORDDTL file doesn't get a match in the ITMMAS file, then the line just doesn't show. And in fact, in the example above, a fourth line does exist, except it has no item number. To see it, we have to change our JOIN to a LEFT OUTER JOIN. At that point, we'll find ourselves in the Land of the Null Value. Here's the statement and the result:

SELECT ODORD, ODLINE, ODITEM, IMDESC FROM

ORDDTL LEFT OUTER JOIN ITMMAS ON ODITEM = IMITEM

ODORD ODLINE ODITEM IMDESC

230,045 1 ITEMA Item A

230,045 2 ITEMB Item B

230,045 3 ITEMC Item C

230,045 4 -

230,050 1 ITEMA Item A

230,050 2 ITEMC Item C

Notice the new fourth line, with the little "dash" for IMDESC. The dash is the universal SQL symbol for "null value," and it means that the item master was not found for the fourth record (which makes sense, since the ODITEM field for that record is blank).

The null value is a strange and awesome thing. It can cause records to be skipped for counting and averaging, it can be used to circumvent referential integrity, it can do all kinds of things. But in this case, it's not very informative. I'm going to show you a simple way to make nulls a little better behaved, and that's the COALESCE statement. Whenever you suspect that you might get a null value and you'd rather see a meaningful default value of your own choosing, you can use the COALESCE to specify that default value. In this case, I want to show "*** NO ITEM" for any item not found. I simply do this:

SELECT ODORD, ODLINE, ODITEM, COALESCE(IMDESC, '*** NO ITEM') FROM

ORDDTL LEFT OUTER JOIN ITMMAS ON ODITEM = IMITEM

And here's the result:

ODORD ODLINE ODITEM COALESCE

230,045 1 ITEMA Item A

230,045 2 ITEMB Item B

230,045 3 ITEMC Item C

230,045 4 *** NO ITEM

230,050 1 ITEMA Item A

230,050 2 ITEMC Item C

Pretty slick, eh?

Showing Unique Values

OK, let's return to the order file. Let's assume that there are more than a couple of orders. Let's assume that many of the orders have the same item number, and what we want is just a list of every item purchased. Well, if all you want is a list of distinct values for one or more fields, SQL has a great keyword: DISTINCT. Let's show the distinct values for item numbers in the example:

SELECT DISTINCT ODITEM FROM ORDDTL

ODITEM

ITEMA

ITEMB

ITEMC

It's hard to tell from the output above, but there are four lines; the fourth line has an ODITEM of blank. Anyway, this is your list of unique values. And if you want to add the description, you can do so:

SELECT DISTINCT ODITEM, IMDESC FROM

ORDDTL JOIN ITMMAS ON ODITEM = IMITEM

I'll leave that one as an exercise for you. Set up some files and see what happens when you combine DISTINCT with a JOIN. Try it on a one-to-many relationship, or try it in combination with LEFT OUTER JOIN (with or without COALESCE).

Aggregating Data

DISTINCT is a powerful keyword, but it provides only a very specific function: creating a list of unique values. What if you need more information, such as in this particular case the number of records for a given item or the total quantity? That's where the GROUP BY syntax comes into play, along with the various aggregation functions. Here's the statement that will do just what we suggested:

SELECT ODITEM, COUNT(*), SUM(ODQORD) FROM ORDDTL

GROUP BY ODITEM ORDER BY ODITEM

ODITEM COUNT ( * ) SUM ( ODQORD )

1 35.000

ITEMA 2 12.000

ITEMB 1 14.000

ITEMC 2 25.000

I've introduced a couple of new concepts. First, the COUNT(*) and SUM(ODQORD) entries in the field list are aggregation functions. The first provides a count of all the rows for the group, while SUM(ODQORD) accumulates the value of the ODQORD field. You might want to know what defines the groups. Well, that's the function of the GROUP BY clause, which in this case groups the results by item number. So you can see that in this file there are currently two records for ITEMA, with a total quantity of 12.000.

OK, now I get to show you a couple of ease-of-use tricks. Note that in this case the SQL values are suddenly very wide. In fact, I've actually deleted many of the spaces in order to get the lines to fit. That's because SQL tends to be very careful and define aggregate fields with huge numbers of digits, just in case. Also, the names of the columns are the rather unwieldy clauses that were used to define the aggregate fields. Let me show you a trick to address both of those issues at once:

SELECT ODITEM,

DECIMAL(COUNT(*),5,0) AS LINES, SUM(ODQORD) FROM ORDDTL

DECIMAL(SUM(ODQORD),12,3) AS TOTAL_QTY

FROM ORDDTL GROUP BY ODITEM ORDER BY ODITEM

Your new data will look like this:

ODITEM LINES TOTAL_QTY

1 35.000

ITEMA 2 12.000

ITEMB 1 14.000

ITEMC 2 25.000

Notice that the columns are much closer and that they have more meaningful names. The DECIMAL clause allows you to specify a number of digits and decimal places for your aggregate functions, while the simple AS clause lets you provide your own name. Of course, the tradeoff is that you have to do a lot more definition in your code. As you need more formatting in your SQL, you need more verbiage, and SQL is nothing if not verbose. That's why I'm still in favor of using SQL as the model in a traditional model-view-controller (MVC) architecture and using something (anything!) else as the view.

One other new addition is the ORDER BY clause. Please note that while various functions may seem to force the data into a particular order, SQL is never guaranteed to deliver the data in any sequence unless you specify it with the ORDER BY clause. This may sometimes seem counter-intuitive, but you should get into the habit of always specifying an ORDER BY clause in any situation where the order of the data is significant, and in business that's just about any situation.

Qualifying Fields

I'm running out of room, but I promised you that I'd show you how qualified names work. To do that, let me use a slightly different example: customers and corporate customers. Often in real applications, customers are grouped under a higher-level customer for accounting or reporting purposes. One way of doing this is to specify a field called a "corporate customer." This is usually a second customer number within the customer master file, and it might look something like this:

A R CUSMASR

A CMCUST 6 0

A CMCORP 6 0

A CMCOMP 3 0

A CMNAME 50

This file has a customer number and name, as well as a company number (not germane to this discussion) and a corporate customer number. So let's say we had an umbrella customer of Costco for the corporate account and then a separate customer number for each individual store. Well, if I wanted to show the corporate customer and its children, I might try something like this:

SELECT CMCUST, CMNAME, CMCORP, CMNAME

FROM CUSMAS JOIN CUSMAS ON CMCORP = CMCUST

However, the first thing I would see is an error message stating "Duplicate table designator CUSMAS not valid." Instead, I have to alias the names so that the SQL processor can distinguish between the parent and the child values.

SELECT CORP.CMCUST, CORP.CMNAME, CUST.CMCUST, CUST.CMNAME

FROM CUSMAS CORP JOIN CUSMAS CUST ON CUST.CMCORP = CORP.CMCUST

What I've done is rename the two versions of CUSMAS, the left-hand side being called CORP, the right-hand side being called CUST. Once that's in place, I then have to qualify each of my field references, since the SQL processor needs to know which side, left or right, to get the value from. Once I've done that, though, the system will happily provide me with the list of customer relationships:

CMCUST CMNAME CMCUST CMNAME

100,000 Costco - Corporate 100,200 Costco - Schaumburg

100,000 Costco - Corporate 100,150 Costco - Glenview

100,000 Costco - Corporate 100,250 Costco - Bloomingdale

100,000 Costco - Corporate 100,300 Costco - Niles

100,000 Costco - Corporate 100,100 Costco - Lake Zurich

You may have noticed, by the way, that I cheated a little bit; I shortened the length of the corporate customer name. Otherwise, it would have taken up way too much space. Also, the children are returned in no particular order; you might recall from earlier in the article that this is because I didn't specify an ORDER BY clause.

What About RDi?

I'd be remiss, of course, if I didn't mention the benefits of Rational Developer for i for SOA Construction (RDi-SOA) for SQL processing. RDi-SOA contains the Data Perspective, which is a graphical interface for creating and executing SQL statements. The interface is very familiar to those who have used other SQL clients and also to those who are familiar with the Eclipse and Rational product lines.

The tools within the Data Perspective are more advanced than those available in the green-screen. While SQL does a very good job within the confines of the 24x80 green-screen paradigm, the graphical assistance capabilities of the Eclipse product line show through pretty well.

Here, for example, is the wizard-generated Data Definition Language (DDL) source for a file that was created using DDS source and the standard CRTPF command:

DROP TABLE PSCDMOMN.ORDDTL

CREATE TABLE PSCDMOMN.ORDDTL (

ODORD NUMERIC(10 , 0) NOT NULL,

ODLINE NUMERIC(4 , 0) NOT NULL,

ODITEM CHAR(15) NOT NULL,

ODQORD NUMERIC(9 , 3) NOT NULL,

ODQREM NUMERIC(9 , 3) NOT NULL,

ODXAMT NUMERIC(9 , 2) NOT NULL

)

LABEL ON TABLE PSCDMOMN.ORDDTL IS 'Order Detail'

LABEL ON COLUMN PSCDMOMN.ORDDTL.ODORD TEXT IS 'Order Number'

LABEL ON COLUMN PSCDMOMN.ORDDTL.ODLINE TEXT IS 'Line Number'

LABEL ON COLUMN PSCDMOMN.ORDDTL.ODITEM TEXT IS 'Item Number'

LABEL ON COLUMN PSCDMOMN.ORDDTL.ODQORD TEXT IS 'Qty Ordered'

LABEL ON COLUMN PSCDMOMN.ORDDTL.ODQREM TEXT IS 'Qty Remaining'

LABEL ON COLUMN PSCDMOMN.ORDDTL.ODXAMT TEXT IS 'Extended Amount'

This is pretty impressive. I had actually thought about writing a tool to build DDL until I found the simple menu option within the Data Perspective that does it for me.

The biggest bad news about this is the fact that the Data Perspective is not included as part of the base RDi product, although we've pleaded with IBM to do so. It seems to me that if you want to get RPG programmers off of the green-screen, you need to provide them with an alternative to STRSQL, and the Data Perspective is just that (and a whole lot more!). However, as of this writing, you still need to license the RDi-SOA to get the Data Perspective functionality.

Final Word

I hope you were able to get some practical use out of this article. As you can probably guess, I've only just begun to scratch the surface. Of the tasks I mentioned at the beginning of the article, I've only managed to touch on analysis and aggregation, and not even those very deeply. If there's interest, I'll continue this series with some more practical examples. I'm looking forward to your feedback.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online