The goal of this series of excerpts on Ruby and IBM i is to first ground you in the Ruby language. That won’t be easy because Ruby is probably about as different from RPG as an apple is from an orange. They are both fruits, but one must be peeled before eating and they taste very different. We are going to first “peel” Ruby so you can understand how it works.

Editor's Note: This article is excerpted from chapter 6 of Open Source Starter Guide for IBM i Developers, by Pete Helgren.

That means a grounding in OO principles. Then we can move on to basic language syntax, access to PASE resources, DB2 for IBM i database access, and then calling RPG programs from Ruby. That’s quite a bit to cover. Ready? Let’s go!

Every programmer wants to achieve the greatest amount of work in the least amount of time and have fun doing it. At least, I hope that’s what you’re after. The programming world rotates on productivity, and that’s what Ruby is designed for. It frees you to produce useful solutions that are easy to write and maintain. Give that some thought for a minute, and then let’s take a common construct like a collection of “stuff.” An array is basically a listing or grouping of separate but similar things. Very often, you want to access those items individually, and usually you want to do it sequentially. So iterating through these items is something you often do. It would seem logical that a container of these items would “know” what is in “itself” and be able to list those items. Being able to tell the container “list these items” would be a handy feature of the container. Something like this:

My tool bench has these items: hammer, saw, old underwear (yeah—rags), screwdriver, empty cans, vise, pliers. What if the tool bench itself could enumerate and access those items? Maybe something like an each function? So, for each item on the bench, what exactly would the function do? Whatever you told it to do! So we’d end up with a few functions that we often do for the tool bench “collection.” Enumerate each item and maybe use a find function (useful for my tool bench). Functions built around that container would maybe look like bench.each and bench.find, where you’d have an operator on the object itself. Ruby ends up looking just like that in many cases because it operates on the principle of least surprise (or astonishment, in this case), which results in a tidy acronym of POLA. In a POLA world, what you expect to see is what you do see.

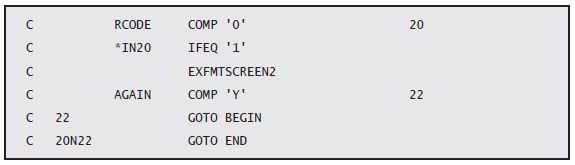

In the IBM i world, that is not always the way languages and/or commands work. Sometimes it is a POLA opposite. Anyone who made the transition from the S/38 to the AS/400 had to rethink some commands. In many cases, AS/400 commands operated on POLA principles, but not always. And then, once you were in RPG, things were not always so predictable. Take a look at a bit of fun RPG II code:

It isn’t immediately apparent just what this code does, and it’s probably unfair to compare a procedural language to an OO one. I will say that free-format RPG is much more coherent to me, and is easier to transition to, than the RPG II above. Then again, RPG I is more readable than assembly language (which I was completely spared from ever having to learn). Bottom line: the principle behind Ruby is POLA, and it does a pretty good job. In fact, it does such a good job that initial forays into the language can be

Moving to a predictable environment from an unpredictable one can be just as disorienting as the opposite approach. When I moved to Salt Lake City from Chicago, the grid-style layout of the streets in Salt Lake left me dumbfounded until I adapted to the Salt Lake way of navigating. After 20 years, you could plop me down anywhere in the Salt Lake valley and I could find my way home. Moving from that rigid structure to the rambling roads of San Antonio, I had to turn on my GPS to find my way to the next block. Plop me down a few miles from home in San Antonio, and I’d be lost without a GPS. But I have learned new rules and now regularly ignore my GPS and I am fine (“Oh, look, what is an ocean doing so close to San Antonio?”). Bottom line: you can learn this stuff. Ruby operates on POLA. POLA is good!

So, with that brief primer and the established principle of POLA, let’s take a look at some Ruby basics just to get started.

Installation

You will most likely want to have some kind of command line into the world of Ruby, so we have a couple of ways we can go. If you are a Windows, Linux, or Mac person, you can find pretty much all you need at the https://www.ruby-lang.org site. Even if you plan to install PowerRuby on IBM i (which you will find here: https://powerruby.com), you’ll probably still want to have something local so you don’t have to lug that Power Systems box around with you. One of the cool features of open source on IBM i is that, except for RPG-based projects, you can write, compile, test, and deploy projects wherever you want initially. When you’re ready, you can deploy to IBM i and test again in that environment. Basically, you can write code whenever and wherever you want. I find that very productive (and a little invasive in my life).

I won’t go into details on how to install Ruby. There are plenty of tutorials on how to do that (and they are simple), so go ahead and install Ruby on both your development workstation and IBM i (if you have that freedom). The following examples will run anywhere.

IDEs and irb

We haven’t talked about IDEs for Ruby. Frankly, an IDE for Ruby would be like an IDE for CL: I guess it would be cool for syntax checking, but it’s overkill for basically a text editor. In fact, that’s really all you need: a text editor. Notepad, Notepad++, WordPad, LaunchPad (I just made that up)—any kind of pad will do (like back in the 1960s). I use the Sublime Text editor for a couple of reasons: it’s cheap, and I can run the code directly within the editor. There are others, so find one that fits like that comfy 10-year-old shirt you keep in the back of your closet and keep it easy. No reason to get hung up on text editor versus IDE wars.

You have another option for testing small snippets of code or just trying a few lines to get the hang of something: a REPL. Rather than some alter-ego clone, a REPL is a read-eval-print loop terminal, and it can really come in handy when you are just getting started. You usually get a REPL by just invoking the executable. In Ruby, you use the irb (Interactive RuBy) command. It will look like Figure 6.1 if you are a Windows user and have installed Ruby.

Figure 6.1: The Ruby irb command

There isn’t any console support in the CMD window in Windows, so you’ll see that message on the startup of irb.

Here’s a really simple “Hello World” example (dang, I really didn’t want to go there, but we always start with a “Hello World” example), as shown in Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2: Hello World example

The command entry point here is after the line number 001:0 and the greater-than sign (>). And what’s with the =>nil? Well, we asked Ruby to output the string “Hello World” (that is what puts does), and the puts command returns nothing, nada, zilch. Hence, to be different and a little British, it returns “nil.” Nothing to worry about.

We could just keep slamming out commands in irb, but it can get a bit tedious if we are trying to write a complete script. You can end a line with a semicolon (;) to indicate that there is more to come, or if you are in a do block, you can code your little heart out until you end it. But a text editor will make things easier in the long run.

A REPL is cool because you can immediately see the results of your programming, but if you have several lines of code, it can get a little tedious, as you can see in Figure 6.3.

Figure 6.3: Code in a REPL

It might just be easier to stuff the whole thing into a text file. That way, if you fat-finger a couple of lines, you won’t have to laboriously retrieve and edit each line at a time. You can hack the file and be done with it.

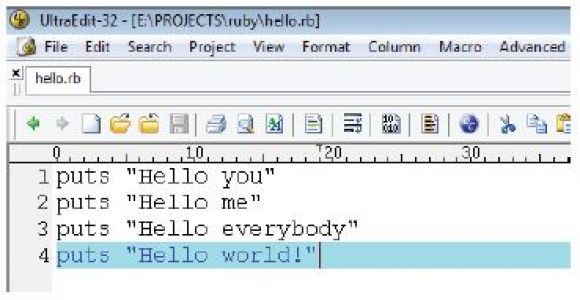

Figure 6.4 shows a snippet of code I knocked out in UltraEdit (I could have used any other editor). It does what I just tediously typed out in irb (except you didn’t see all the correcting going on).

Figure 6.4: The same code in an editor

Going to the command line and typing ruby and the filename will run the script:

But, Ruby really doesn’t give a rip about the .rb file extension. You can run Ruby against any file that has valid Ruby commands in it, like this:

The convention is to use .rb at the end because, in most cases, you have associated the .rb extension with the Ruby binary (in Windows) and a shebang (#!) directive to point to the correct executable (in PASE), and that combination will “know” how to run the script:

But really, as long as you point Ruby to a file with valid syntax, no problemo! Ruby will parse and execute the script.

What if your syntax is problematic? Then what? Let’s make a very subtle (and common) mistake and see what happens. First, the file contents:

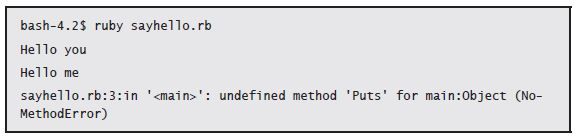

Then run it:

What the heck? Undefined method 'Puts'? We have been “putting” all day. What’s up? Well, Ruby is case-sensitive. Welcome to that world! A host of languages are sensitive to case, and Ruby is one of them. In this case, our script happily executed each line until it got to line three, which had 'Puts' instead of 'puts', and Ruby barfed. Some text editors that have syntax checking can catch this kind of thing (which is a good thing). Distinguishing between 'Puts' and 'puts' is pretty easy, but most text editors, even with highlighting and syntax checking, won’t always give you the correct feedback all the time.

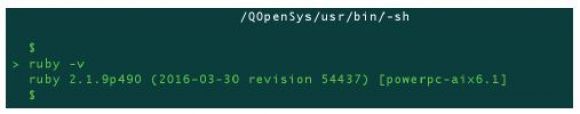

Getting tired of that Windows command window? Well, on the IBM i, we can do something pretty similar. You could start by going to the 5250 command line and starting QSH or QSHELL, but STRQSH, QSH, and QSHELL start a PASE (UNIX)-like environment shell that really wasn’t designed to run AIX programs (so don’t bother). You could also run QP2TERM, which is a shell that is a more AIX (PASE)-friendly environment. Figures 6.5 and 6.6 offer a quick look at some of the results of using the two shells and invoking Ruby.

Figure 6.5: QSHELL invoking Ruby

Yikes! Probably not a good idea to continue.

Figure 6.6: QP2TERM invoking Ruby

That’s more like it!

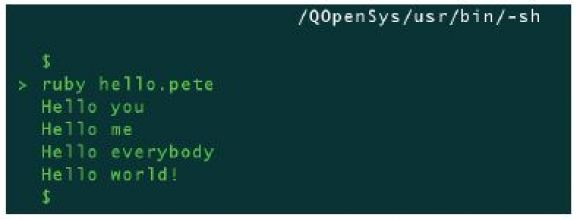

If we copy a Ruby script file over to the IFS and run it, we get the same results as we did in Windows, as shown in Figure 6.7.

Figure 6.7: Running Ruby from the IFS

An easier way, IMHO, is to use a TTY terminal emulator like PuTTY and use Secure Shell (SSH) to connect to your IBM i. You'’ll have all of the functionality of QP2TERM without the overhead of also running a 5250 emulator (although TTY is basically a terminal emulator).

I use PuTTY for my access to PASE, but there are plenty of free alternatives. Figure 6.8 shows what the script in Figure 6.7 looks like in PuTTY (and BASH).

Figure 6.8: Using PuTTy and BASH

Boringly similar to all the other scripts and REPL examples we have looked at, isn’t it?

So that’s a very basic first step toward using a REPL like irb and executing scripts at the command line. So far, it’s pretty easy.

Next, we need to take a look at a few more programming constructs before stepping back to examine classes and modules.

Most of the Ruby language constructs follow a predictable pattern that we, as programmers, are familiar with. It is the implementation of those constructs that can make the “getting started” step a bumpy ride. So let’s get on the horse and ride!

Next time: Language Basics. Want to learn more? You can pick up Peter Helgren's book, Open Source Starter Guide for IBM i Developers at the MC Press Bookstore Today!

More than ever, there is a demand for IT to deliver innovation. Your IBM i has been an essential part of your business operations for years. However, your organization may struggle to maintain the current system and implement new projects. The thousands of customers we've worked with and surveyed state that expectations regarding the digital footprint and vision of the company are not aligned with the current IT environment.

More than ever, there is a demand for IT to deliver innovation. Your IBM i has been an essential part of your business operations for years. However, your organization may struggle to maintain the current system and implement new projects. The thousands of customers we've worked with and surveyed state that expectations regarding the digital footprint and vision of the company are not aligned with the current IT environment. TRY the one package that solves all your document design and printing challenges on all your platforms. Produce bar code labels, electronic forms, ad hoc reports, and RFID tags – without programming! MarkMagic is the only document design and print solution that combines report writing, WYSIWYG label and forms design, and conditional printing in one integrated product. Make sure your data survives when catastrophe hits. Request your trial now! Request Now.

TRY the one package that solves all your document design and printing challenges on all your platforms. Produce bar code labels, electronic forms, ad hoc reports, and RFID tags – without programming! MarkMagic is the only document design and print solution that combines report writing, WYSIWYG label and forms design, and conditional printing in one integrated product. Make sure your data survives when catastrophe hits. Request your trial now! Request Now. Forms of ransomware has been around for over 30 years, and with more and more organizations suffering attacks each year, it continues to endure. What has made ransomware such a durable threat and what is the best way to combat it? In order to prevent ransomware, organizations must first understand how it works.

Forms of ransomware has been around for over 30 years, and with more and more organizations suffering attacks each year, it continues to endure. What has made ransomware such a durable threat and what is the best way to combat it? In order to prevent ransomware, organizations must first understand how it works. Disaster protection is vital to every business. Yet, it often consists of patched together procedures that are prone to error. From automatic backups to data encryption to media management, Robot automates the routine (yet often complex) tasks of iSeries backup and recovery, saving you time and money and making the process safer and more reliable. Automate your backups with the Robot Backup and Recovery Solution. Key features include:

Disaster protection is vital to every business. Yet, it often consists of patched together procedures that are prone to error. From automatic backups to data encryption to media management, Robot automates the routine (yet often complex) tasks of iSeries backup and recovery, saving you time and money and making the process safer and more reliable. Automate your backups with the Robot Backup and Recovery Solution. Key features include: Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online