RPG IV provides a rich set of built-in functions, many of which target data manipulation tasks. Read Part One.

Editor's Note: This article is excerpted from chapter 8 of Free-Format RPG IV: Third Edition, by Jim Martin.

In this excerpt series, we explore those options, which include assignment statements, a large stable of built-in functions, and operations for converting dates and times.

Built-in Functions

Built-in functions let us perform data-type conversions, substringing, concatenation, and many other operations. If you have data that you want to transform from one form to another, odds are there is a built-in function available to make the job easier.

In the remainder of this excerpt, we look at the numerous built-in functions available to perform data manipulation functions in free-format RPG IV. Table 8-1 lists these functions, along with a brief description of each one.

|

Table 8-1: Built-in functions for data manipulation |

|

|

Built-in function |

Description |

|

%Char |

Convert to character data |

|

%Check |

Check characters |

|

%Checkr |

Check reverse |

|

%Date |

Convert to date |

|

%Days |

Number of days |

|

%Dec |

Convert to packed decimal format |

|

%Dech |

Convert to packed decimal format with half adjust |

|

%Decpos |

Get number of decimal positions |

|

%Diff |

Difference between two date, time, or timestamp values |

|

%Editc |

Edit value using an edit code |

|

%Elem |

Get number of elements |

|

%Hours |

Number of hours Continued |

|

Table 8-1: Built-in functions for data manipulation (continued) |

|

|

%Int |

Convert to integer format |

|

%Inth |

Convert to integer format with half adjust |

|

%Len |

Get or set length |

|

%Minutes |

Number of minutes |

|

%Months |

Number of months |

|

%Mseconds |

Number of microseconds |

|

%Replace |

Replace character string |

|

%Scan |

Scan for characters |

|

%Scanrpl |

Scan and replace characters |

|

%Seconds |

Number of seconds |

|

%Size |

Get size in bytes |

|

%Subdt |

Extract a portion of a date, time, or timestamp |

|

%Subst |

Get substring |

|

%Time |

Convert to time |

|

%Timestamp |

Convert to timestamp |

|

%Trim |

Trim characters at edges |

|

%Triml |

Trim leading characters |

|

%Trimr |

Trim trailing characters |

|

%Uns |

Convert to unsigned format |

|

%Unsh |

Convert to unsigned format with half adjust |

|

%Xlate |

Translate |

|

%Years |

Number of years |

Converting Decimal to Character

Often, data is in the wrong data type for what we want to do. Before IBM gave us built-in functions, we used a Move or MoveL operation to convert a decimal field to character. Free format provides no Move or MoveL operation, but the built-in function %Char does what we need. The %Char function takes a numeric operand and returns it as a character string.

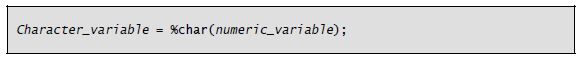

The general form of the %Char built-in function is as follows:

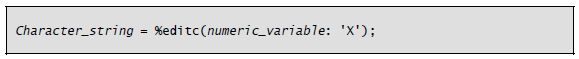

A quirk of %Char is that leading zeros in the numeric field are converted to blanks (the numeric field is zero suppressed). To convert the numeric field to a character string that includes the zeros in the result, use the %Editc built-in function with the X edit code. The general form of the %Editc built-in function is as follows:

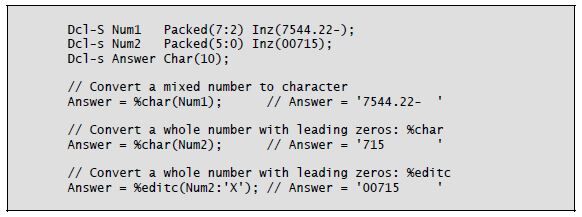

Listing 8-3 illustrates converting numeric data to character using these functions.

Listing 8-3: Converting numeric to character using the %Char and %Editc built-in functions

Converting Character to Packed Decimal

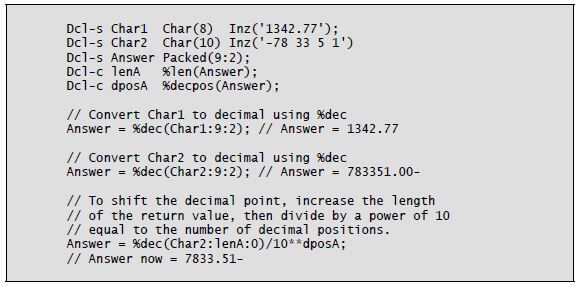

Converting character data to numeric assumes that the character data is numbers, with or without a decimal point, and possibly with a negative sign. The %Dec built-in function uses three parameters to convert a character string to packed decimal. The half-adjust version of %Dec is %Dech.

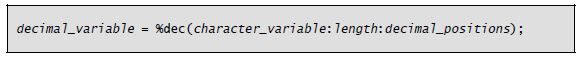

The general form of the %Dec function is as follows:

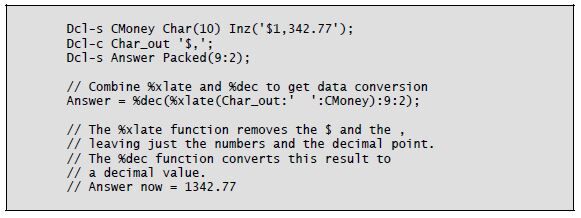

The function’s first parameter is the character string to be converted. This parameter can be a date, time, or timestamp in addition to a character string. The character string can include a plus sign (+) or a minus sign (–) at either end, as well as a decimal point (.) or a decimal comma (,). You must remove any currency symbol, thousands separator, or asterisks from the character string before the conversion. The %Xlate built-in can perform this task nicely within the %Dec expression.

The %Dec function’s second parameter is the length of the return value. The third parameter is the number of decimal positions in the return value. These two parameters can be literals or named constants but cannot be other built-in functions.

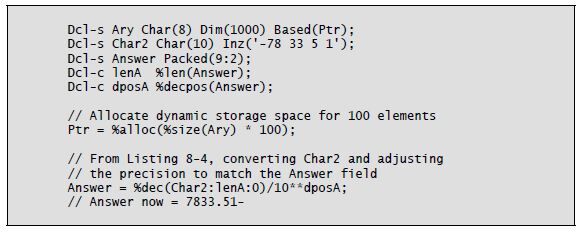

The examples in Listing 8-4 demonstrate the possibilities. Notice the use of two additional built-in functions, %Len and %Decpos, in this code. These functions retrieve the numeric result field’s length (%Len) and number of decimal positions (%Decpos).

Listing 8-4: Converting character data to decimal using the %Dec built-in function

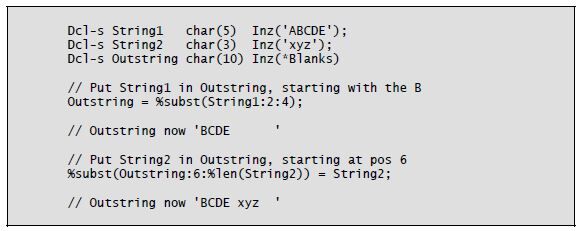

Substringing

Using the %Subst built-in function, you can specify substringing for a “source” string (i.e., a string on the right side of the equal sign) or for a “target” string (i.e., a string on the left side of the equal sign). %Subst is nearly identical to the CL built-in %SST and is also similar to RPG’s Subst (Substring) operation. The return value of %Subst is a character string. The function’s three operands are a character string, a starting location, and a length. If insufficient characters are available in the string at the specified starting location for the given length, the compiler issues an exception.

To substring a target string, you specify %Subst and its operands on the left side of an assignment statement. The location and length become the new home of the data string that is being sent by the right side of the assignment statement.

Listing 8-5 shows examples of substringing.

Listing 8-5: Substringing using the %Subst built-in function

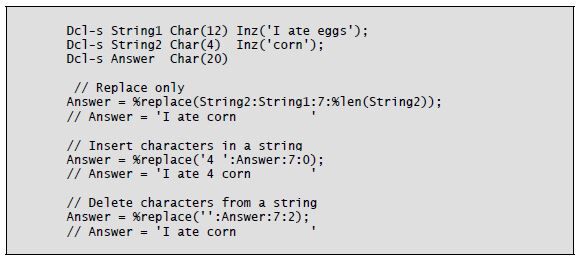

Replace

The %Replace built-in function has no counterpart in CL or RPG operation codes. This powerful built-in uses four operands and has several capabilities. It can delete characters from a string (only), insert characters from one string into another string (only), and delete characters and insert characters. When inserting, all of the characters in the first parameter are inserted, regardless of the parameters specifying starting location and length. The big difference between %Subst and %Replace is that %Replace uses two character-string operands: a “from” and a “to.” The resulting character string is the return value, so the operation modifies neither operand.

The %Replace function’s third operand is the starting location in the “to” operand. The fourth operand is the length. Using a zero (0) length for the fourth operand enables the insert function. Using a null—that is, two apostrophes (') together—as the first operand enables the delete function.

Listing 8-6 illustrates use of the %Replace built-in function.

Listing 8-6: Using the %Replace built-in function

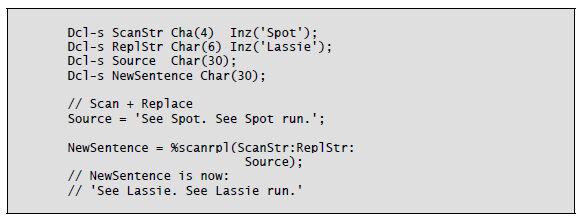

Scan and Replace

The %Scanrpl built-in function is new to RPG IV in V7.1. It returns a character string in which all occurrences of a scan string are replaced in a source string with a replacement string. That’s a lot of function in a small package. The general idea of this built-in-function is to find a given small string in a larger string and replace all the occurrences with a replacement string. The replacement string can be smaller, equal to, or larger than the scanning string.

The %Scanrpl function uses five parameters. The first is the scanning string, the second is the replacement string, and the third is the source string. The fourth parameter (optional) is the starting location of the scan and replace, and the fifth (also optional) is the length of source string to be scanned/replaced. The default starting location is position 1, and the default length is the remainder of the source string starting from the starting position.

By specifying two apostrophes together for the second parameter, you can remove the scanning string from the source string.

Listing 8-7 illustrates use of the %Scanrpl built-in function.

Listing 8-7: Using the %Scanrpl built-in function

Concatenation and Trim

The character string operator + replaces RPG’s Cat operation code in free format. The + operator performs concatenation only; it does not trim blanks, as the Cat operation does. If you want to produce output strings containing several fields intermixed with constants and having a sentence or message look, you will need to use the %Trim built-in function.

The %Trim built-in function trims blanks in three variations:

- %Trim removes both leading and trailing

- %TrimL removes leading

- %TrimR removes trailing

Each of these three built-in functions uses a single character-string operand and returns the same character string without the blanks. If a character string contains an intermediate blank (e.g., 'San Antonio'), that blank is not removed.

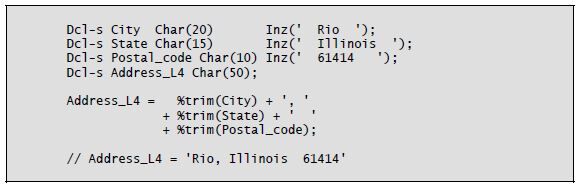

Listing 8-8 shows examples of concatenation and trimming.

Listing 8-8: Concatenation and blank trimming using %Trim

Converting Character to Integer

Another helpful built-in for data-type conversion is %Int. The original purpose of the %Int built-in function (and its companion, %Inth) was to extract the whole number part of a mixed number. The %Inth variation performs the same function as %Int and half-adjusts.

In a later release, IBM improved %Int and %Inth, letting the parameter be a character string or an expression. The character string can include a plus or minus sign at either end and a decimal point or decimal comma. Blanks, which can appear anywhere in the character string, are ignored.

The %Int and %Inth functions can also extract the whole-number portion of a floating-point variable. However, you cannot use a floating-point constant (e.g., 7.4E3).

You can use the result of a %Int or %Inth expression in a program wherever an integer is expected—in array indexes, length values, or loop parameters, for example. Be careful, though, because the result can be a negative integer.

Another built-in function, %Uns, is equivalent to %Int but works only with positive numbers. Its companion, %Unsh, performs the half-adjust function.

As with %Int, these functions truncate all decimal positions. The %Uns or %Unsh function may be a better choice for setting array indexes, lengths, or loop parameters because the result is always a positive number.

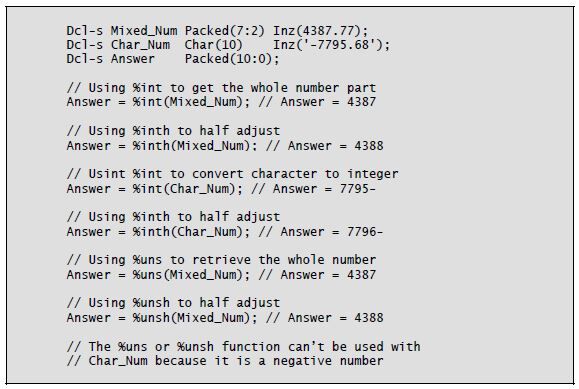

Listing 8-9 shows examples of %Int, %Inth, %Uns, and %Unsh.

Listing 8-9: Using %Int, %Inth, %Uns, and %Unsh built-in functions

Extracting Size, Length, and Decimal Positions

Data manipulation would be difficult without the built-in functions %Size, %Len, and %Decpos. Free-format RPG IV programmers make frequent use of these functions, not only for the handy functionality that they provide but also to avoid future “bugs.” Programs that use %Size, %Len, and %Decpos are less prone to error when changes are needed (similar to the keyword *Like in definition specifications).

The %Size built-in function returns the number of bytes of its first argument. You use a second operand, *All, with arrays, tables, and multiple-occurrence data structures to calculate the total size of these items. It is important to remember that the %Size return value is the number of bytes, not the length. For character variables, size and length are equivalent, but for most numeric variables, the size is a different value than the length.

The %Len built-in function uses one parameter, a variable or expression, and returns the length. For character variables, this length is the size in bytes. For numeric variables, it is the defined number of digits. Other built-in functions, such as %Subst and %Replace, often require the length of a variable.

You can also use the %Len function in For groups to condition the stopping point when iterating through positions in a variable. Coding with %Len gives you the flexibility to automatically change a variable or parameter value instead of using constants, thus avoiding the need to make many program changes when a variable’s length changes.

Another use of the %Len function is to set the current size of a variable-length character variable. Use %Len on the left side of an assignment statement with the new length as the value on the right side.

The %Decpos built-in function uses one numeric (non-float) parameter. It returns the number of decimal positions of the parameter as an integer. The parameter can be an expression, but float variables are not permitted.

Listing 8-10 illustrates the use of %Size, %Len, and %Decpos.

Listing 8-10: Using %Size, %Len, and %Decpos built-in functions

Number of Elements

You use the %Elem built-in function with tables, arrays, or multiple-occurrence data structures to determine the number of elements. You can use this built-in function as a value in a definition specification keyword or specify it as a factor in a procedure operation. As with %Len and *Like, %Elem can help you avoid future errors (e.g., by using it to control loops). If the number of elements in the definition for an item changes, then the %Elem value changes throughout the program. Using this built-in function to control For groups and other program functions is a factor in good program design.

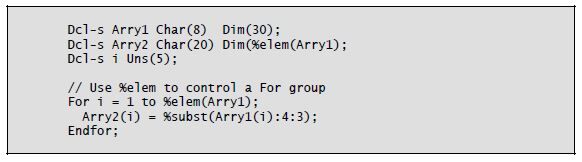

Listing 8-11 illustrates how to use the %Elem built-in function.

Listing 8-11: Using the %Elem built-in function

Looking for Something?

Three built-in functions provide assistance in finding a character in a character string. The %Check built-in function works the same as RPG’s Check operation code. For the function’s first parameter, you specify one or more characters as a literal or named constant. This character list is also called a comparator. The second parameter is the character string to be searched. The third parameter, which is optional, is the position in the second parameter at which the search should begin. If you omit the third parameter, the starting position defaults to 1 (one). The %Check function searches the string (parameter 2), looking for the first occurrence of a character that is not in the comparator (parameter 1). If a character is found, the search ends and the return value (an unsigned integer) is set to the position in the string where the character was found. The function returns a 0 if no character is found.

The %Checkr built-in function is the equivalent of the CheckR operation code.

It uses the same three parameters as %Check but by default starts at the last position of the second parameter. The search is performed from right to left until either a character is found that is not in the parameter 1 list or the end of the string is reached. The return value is set to the position in the character string where a character is found or to 0 if no character is found.

The %Scan function is another built-in that replaces an operation code—in this case, Scan. The %Scan function’s first parameter is a search argument. It is a character string of one or more characters specified as a literal, named constant, or variable. The second parameter is the source string to be searched. The third parameter, which is optional, is the starting position in the second parameter for the search. If you omit the third parameter, the starting position defaults to 1. The %Scan function searches the source string (parameter 2), looking for the first occurrence of a character (or characters) that exactly matches the search argument. The return value is the position in the source string where the search argument was found, or 0 if no match occurs.

One feature of the Scan operation code is the return of multiple found positions (in one scan) into array elements. The %Scan built-in function does not provide this function.

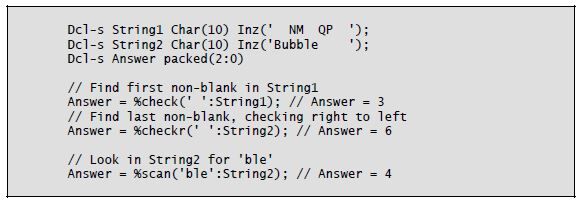

Listing 8-12 shows examples of %Check, %Checkr, and %Scan.

Listing 8-12: Examples of %Check, %Checkr, and %Scan built-in functions

String Translation

Another data-manipulation task performed in RPG is translating characters in a string from one character to another. The built-in function %Xlate replaces RPG’s Xlate operation code in performing this task. The first parameter of %Xlate is the “from” character list. The second parameter is the “to” list. The function makes a one-to-one relative match between the “from” list and the “to” list. The third parameter is the character string to be translated. The fourth parameter is optional and defaults to 1 if not specified; it is the starting position of the translation in the character string.

The %Xlate built-in works as follows: The first character in the source string is compared with each character in the “from” list. If a match is made, the char- acter in the “to” list with the same relative location as the “from” list replaces the character used in the search. If no match is found, the character in the source string is not translated. The output character (translated or not) goes to the return value string. The return value string is built left to right. The next character in the source string is run through the process, then the next, and so on until all characters in the source string have been processed.

Listing 8-13 shows a sample use of the %Xlate built-in function.

Listing 8-13: Using the %Xlate built-in function

Combining Built-in Functions

Using one built-in function within another built-in function may seem a little awkward at first. As RPG programmers, we have been conditioned to break down everything into one step per operation. That is the way RPG was designed at its inception in the early 1960s. RPG IV, though, lets us code character and numeric expressions in the extended Factor 2. There goes one step per operation, right out the door!

As you’ve seen in the code examples, built-in functions often permit a parameter to be the return value of another built-in function. And within the second built-in function, a parameter can be yet another built-in function. Where does this end? Good programming style dictates keeping built-in nesting to a minimum. Our C-language brethren have already hashed out these issues because they use many more functions than we do.

At one end of the spectrum is the practice of using only one function (in our case, built-in function) per line of code. Doing so makes programs easier to read, but it takes more “work” variables. The opposite approach is to nest functions as much as possible. This strategy cuts down on the number of “work” variables and total lines of code. Unfortunately, it also creates very complex program statements. Another problem is that the debugger utility will not reveal the values of nested built-in functions.

The solution for all of us lies somewhere in between: Use some nesting, but limit it to two or three levels. Although it is tempting to use more levels, we need to constrain ourselves for the sake of the maintenance programmers who must read and modify our code.

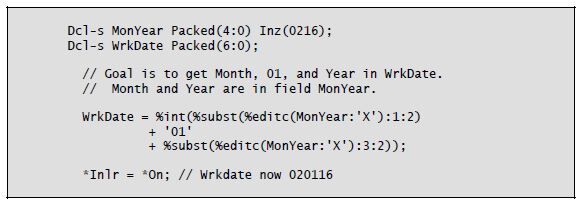

You can see examples of built-in function nesting in Listings 8-5, 8-6, 8-10, and 8-13, as well as in Listing 8-14 below.

Listing 8-14: An example of triple nesting of built-in functions

Next time: Part 3 - Date and Time Operations. Can't wait? You can pick up Jim Martin's book, Free-Format RPG IV: Third Edition at the MC Press Bookstore Today!

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online