While helping my son prepare for his fourth-grade midterm history exam, I traveled through three millennia and two continents in only 30 pages. These pages contained an account of the advances and breakthroughs that cultures underwent in the technology their information systems employed through the millennia. Using a little imagination, I could read between the lines. I could see how the Phoenicians could have made lots of money if they had IPOed a company to exploit their alphabet, since it was the first one on the market. I could see that the Persians should have copyrighted their numbers so they could license them to the rest of the world. I could see why the Babylonians used clay tablets for their mass storage units while the Chinese used papyrus.

Well, humanity is doing it again. We have come upon a new major breakthrough: Extensible Markup Language (XML).

Simple as 1, 2, 3 or A, B, C

Just like numbers and letters, XML took some time to develop. It is so powerful that, also just like numbers and letters, it revolutionizes environments where it is applied. However, it is so simple that even children can learn it.

First, look at the simplicity of XML. Figure 1 shows an example of a trivial XML invoice. Check out the invoice and judge for yourself the simplicity of this XML document. As you can see from this example, reading documents formatted in XML is easy for both humans and computers. Although the invoice is verbose, you can easily tell what each piece of data represents. For example, it is clear that "Austin" is the city to deliver items to and not the name of a person. You also don't need to guess that "Datagate/400" is the description of the second item on the invoice.

Like a human brain determining the valuable parts of information in a document, a computer program can parse an XML document to extract relevant information just by looking at it. Operating systems, programming languages, and components are equipped to assist in the parsing and validation of a document, just as they are equipped to assist in the handling of database files. Some examples of these kinds of support are Microsoft's MSXML ActiveX, IBM's XMLJ4 parser for Java, and ASNA's Externally Described

XML Schemas for Visual RPG. Unfortunately, most documents on the Web today are formatted using HTML and not XML.

HTML: Another Page in History

To understand the present, we first need to understand the past. Therefore, before I continue with XML, I should review the development of the Web and show you how the stage has been set for what are being called business-to-business processes. Then, you'll see why XML is the lead character in this new chapter of Web development.

The "Web experience" can be explained in very simplistic terms as a gigantic process of file transfers. A user sitting in front of a Web browser on a client machine requests a page from a server machine by providing the complete address of a file in this general form: //ServerName/Path/FileName

Once the client machine receives the file, the browser analyzes the file type and takes the proper action depending on the kind of file it receives. It can save the file to disk, display the file in a window, or even execute the file.

The majority of files transferred on the Web are documents in a format called hypertext markup language (HTML). This format was designed to describe how to display a document on a browser's window. The document's author embeds "tags" within text that mark the beginnings and ends of sections. These tags state that particular sections are to be shown in particular styles. For example, the author can specify what font to use or whether to bold or italicize certain characters. The tags can also designate that another file containing an image is to be embedded in a certain position of the document. One tag is even used to indicate to the browser that a link to another document is to be shown in the window. In addition, there are tags for titles, headings, tables, colors, and various other instructions that enable the author to describe exactly how a document is to be shown on the client's screen.

New technologies evolved that allowed the contents of Web documents to be easily and dynamically generated. Today, documents have all kinds of information, many of them with data coming directly from online databases. This development has effectively transformed the Web into a huge online system where the Web browser plays the part of the terminal and users can run applications residing on Web servers to get information they desire. For example, users can obtain real-time quotes for their favorite stocks, the current temperature of their travel destination, and prices and availability information for airline tickets. Using these kinds of self-serving applications, users can also enter data directly into the systems of Web sites they visit.

A couple of years ago, most corporations were discovering the importance of the Web and the need to be present in this new environment. Today, those who don't already have a presence on the Web are hurrying to create one. The first step that most have taken is to put their company brochures on their Web sites for their customers to view. Many of them also have plans to broadcast their data live on the Web. Another new discovery by businesses is that they can obtain much of the information they need from their suppliers, customers, and partners directly from their corresponding Web sites. The Web is effectively transforming the way companies carry on their businesses and processes.

Right Information, Wrong Format

Last Christmas, I visited several toy Web sites, looking for a particular game. I found four Web sites carrying the game, but it was out of stock on two of the sites, and the other two sites had a difference in price of $3. Obtaining all of this information took about 20 minutes. I can only imagine the tedious task of a professional buyer, and I'm referring not to your typical teenage mall shopper but to a corporate buyer having to go through the same process I went through. I had to use four different applications, each with its own quirks and specific ways of accessing and displaying the information requested.

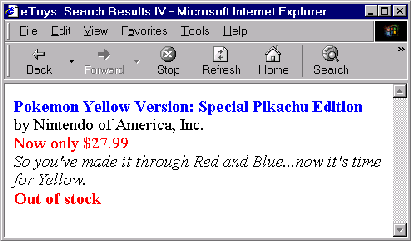

I'll now look at a simplified page of a Web site showing the price and availability of an article for sale. Figure 2 shows the rendering on the browser's window, and Figure 3 shows the actual HTML source containing the requested toy information. As you can see in Figure 3, most of the markup of the document deals with how the information is to be presented in the browser and not what the data is. For a user viewing this information, it is easy to determine the price of the article and whether or not it is available from this vendor. However, it is much harder to create a generic program to gather this information from Web pages formatted in HTML. We tend to forget how hard it is for a computer program to convert data into relevant information, just because we humans are so good at it. Even very young children extract information from the simplest pieces of data. When a child sees his mother picking up her coat and car keys, the child knows it is time to go out for a ride. When a student gets a paper from his teacher with the letter "F" splattered across it, he knows his work has been rejected. If a shopper sees "$27.99" on a computer screen along with toy information, she knows the price of the toy is twenty-seven dollars and ninety- nine cents, even if the document doesn't say "price" or "cost" anywhere.

Programmers know that computer programs aren't so smart. Programs need to be told exactly what to do and exactly where to get information they need to carry on their algorithms. Current data processing applications get their data from well-structured sources, mostly database and display files. The new generation of applications will also have to obtain data directly from the Web. HTML documents, while good for human consumption, don't have enough information and structure to allow a program to get the information it needs.

So What Is XML?

XML is a format employed to make information in a document self-describing. The standard for XML is controlled by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). Here is the formal description of XML according to its Web site at www.w3.org/TR/1998/REC-xml- 19980210:

Extensible Markup Language, abbreviated XML, describes a class of data objects called XML documents and partially describes the behavior of computer programs which process them....

XML documents are made up of storage units called entities, which contain either parsed or unparsed data. Parsed data is made up of characters, some of which form character data, and some of which form markup. Markup encodes a description of the document's storage layout and logical structure. XML provides a mechanism to impose constraints on the storage layout and logical structure.

And these are the design goals for XML:

1. XML shall be straightforwardly usable over the Internet.

2. XML shall support a wide variety of applications.

3. XML shall be compatible with SGML.

4. It shall be easy to write programs which process XML documents.

5. The number of optional features in XML is to be kept to the absolute minimum, ideally zero.

6. XML documents should be human-legible and reasonably clear.

7. The XML design should be prepared quickly.

8. The design of XML shall be formal and concise.

9. XML documents shall be easy to create.

10. Terseness in XML markup is of minimal importance.

In plain English, these formalities mean that the Web, with the help of XML, can become a huge database system from which we can extract and process information we need to communicate with our suppliers, customers, and partners.

The recent explosive growth of the Internet has created a big infrastructure with servers, routers, communication backbones, and firewalls. This infrastructure could serve a new purpose if programs other than Web browsers could consume data flowing through it. Think for a moment about that common analogy applied to the Internet: the "information superhighway." Suppose that the real asphalt-and-concrete interstate highways were originally created to transport only people using cars. Then, we suddenly got the great idea of using the same highways with a different format, a truck, to move all kinds of goods. Well, that is what is happening now. Just use a different format on the Internet, XML instead of HTML, and voilá! The entire infrastructure can be reused for a whole new purpose.

The kind of platform independence that HTML has obtained is also available for XML. You don't have to execute the Web server or client program on any specific platform, because XML technology is available on any platform. If the platform can produce HTML (and, by now, every modern server platform can), it can produce XML. The same can be said for the platform running the program consuming the data. You can have a mixture of OS/400, UNIX, and Windows machines happily talking to one another in a format common to all.

Another big advantage of XML is that it has the backing of all the major players in the Internet. These are some of the companies participating in the definition of the XML standard: Adobe, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Microsoft, Netscape, and Sun.

For all of these reasons, XML is revolutionizing many areas of IT, including the world of electronic data interchange (EDI). Traditional EDI has a high entry point for newcomers, proportionally higher for small and midsized enterprises. Often, small business partners are forced into buying specific hardware and software from their bigger partners and contracting the service of a specific Value Added Network (VAN) to be allowed to trade with the bigger guys. XML brings the hope of a cheaper and more flexible implementation of EDI for business-to-business. For more information on XML and EDI, visit www.xmledi.com or read the article at www.sunworld.com/sunworldonline/ swol- 02-1999/swol-02-xmledi.html.

Tell It Like It Is

Let me go back to my example of the toy information. If the document were formatted using XML, each piece of data would be labeled with a meaningful tag. For example, the name of the toy would be tagged as

The tags used in the document (

If the schema for a document is known, the document can be validated. Once the document has been validated, an application program can read the document to process its data. For example, a purchaser application could read toy information from multiple vendors to consolidate it into a single window and then sort the articles based on price, manufacturer, availability, or any other criteria.

With XML, you have the ability to construct your own languages. You can define one schema for an invoice, another for purchase orders, and still another for payments. You can even define a schema for word processing documents. HTML is one such language; it defines documents that can be displayed in a browser's window. Now, if you were to create a new browser, you wouldn't invent a new language for your browser. You would stick to the well-known standard, HTML. The same holds true for languages defining purchase orders; there is no need for each company to create its own language. It is much better to have a standard. That way, any company can send any other company a purchase order.

Standards for business documents are being formed today. Having standard tags to refer to the data within a type of document is crucial for business partners to trade data. The process of standardization is being handled very democratically. Individuals and corporations are proposing their own versions of XML schemas for many different document types in public Web sites. When a company uses one of the proposed schemas, it casts its vote for that contender. As time goes by, the most popular schemas will become de facto standards. For a repository of such schemas, visit www.biztalk.org.

Using style sheets, it is possible to convert an XML document from one format to another. This capability is particularly important because data in an XML document can be converted into HTML so it can be rendered in a browser. The conversion can be done by the browser or by the server. Imagine a dot-com toy store being able to develop applications that process XML documents and then allow the generated information to be used directly by its partners' applications and by Web visitors using their browsers. Talk about code reuse!

History in the Making

XML has many areas of application. In this article, I have mentioned only one of the most exciting ones: data exchange through the Internet. However, XML documents can be used to communicate data between two lightly coupled components of an application.

The main pitfall of XML today is that it is still very new. Even though the XML 1.0 standard is stable, there are areas surrounding XML that are still in a state of flux. This is particularly true for schemas and style sheets. Still, XML will revolutionize many areas of the IT industry. We will see a complete new set of EDI applications as well as the next generation of Web applications and sites, so brace yourself for the next chapter of history.

References and Related Materials

• Biz Talk home page: www.biztalk.org

• Sun World’s XML the Future of EDI? Web page: www.sunworld.com/sunworldonline/swol-02-1999/swol-02-xmledi.html

• W3C Extensible Markup Language (XML) 1.0 Web page: www.w3.org/TR/1998/REC- xml-19980210

• XML EDI Web page: www.xmledi.com

Pokemon Yellow Version: Special Pikachu Edition

by Nintendo of America, Inc.

Now only $27.99

So you've made it through Red

and Blue...now it's time for Yellow.

Out of stock

Figure 1: An invoice formatted using XML describes content, not presentation.

Figure 2: An HTML page uses multiple colors and fonts to enhance the display of information.

Figure 3: The HTML source for the document in Figure 2 describes the presentation of information with various colors and fonts.

and Blue...now it's time for Yellow.

Figure 4: If Pokémon information were maintained in an XML document, it could be processed by client software as well as displayed in a Web browser.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online