Editor's note: This article is an excerpt from Mastering IBM i, published by MC Press.

If you tell SQL to retrieve rows that have the same column values, it will do that, duplicating those rows in the result table. For example, if you wanted to list the employee numbers of any employees assigned to any project, you might simply type

Select EMPNO

From PRJMBRPF

But you would soon see that many numbers are repeated in the output—for example, if an employee were assigned to four projects, his or her employee number would appear four times in the output list. You also would notice that employee numbers appeared in no particular order, making it difficult to analyze the list. In fact, because this request uses a single file and requires no index search, the output is ordered by the relative record numbers of the physical file or in arrival sequence, even if the file itself is keyed.

SQL provides the Distinct keyword for eliminating duplicate rows of the result table. You can use the Order By clause at the end of any Select statement to sort the output by one or more sort fields.

Therefore, to correct the above statement, we could type

Select Distinct EMPNO

From PRJMBRPF

Order By EMPNO

Now we would have a sorted list of unique employee numbers. The Order By clause defaults to ascending order (abbreviated Asc), but you can specify descending sequence by using the abbreviation Desc.

Using Order By, we should be able to handle the following request: List all employees by last name, showing department and salary. The output should be sorted by department and then, within department, from highest to lowest salary.

Select DEPT, FIRSTNAME, LASTNAME, SALARY

From EMPPF

Order By DEPT, SALARY Desc

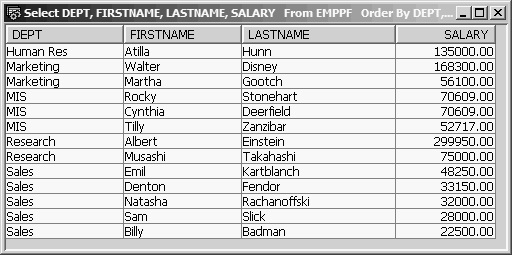

The output in Figure 13.19 shows how the data has been sorted by descending salary within department.

Figure 13.19: EMPPF Data Ordered by DEPT, SALARY Descending

Notice that employees Stonehart and Deerfield are in the same department and have the same salary, but Stonehart comes before Deerfield. This occurs because we did not request sorting by last name; and in the physical file, the Stonehart record has a lower relative record number and so comes first. We could easily fix this problem by adding a third Order By entry for LASTNAME.

Caution: A warning about the use of the Order By clause: It can cause a significant hit on system performance, especially when you are dealing with large files that lack appropriate indexes. Therefore, you should use Order By with caution and only when required.

Column Functions

In addition to the large number of scalar functions available, SQL has some useful column functions. Column functions work on a set of field values as a whole—for example, all SALARY values in the result table—as opposed to scalar functions, which work on a field of each record. To see the difference, consider the following examples.

First, we will use a scalar function that returns a value for each row of the result table:

Select LASTNAME, SALARY, Decimal(SALARY * 1.035,7,0)

As NEW_SALARY

From EMPPF

The Decimal scalar function is useful to format a calculated value to a fixed precision (total digits) and scale (number of decimal digits). Its syntax is

Decimal (expression, precision, scale)

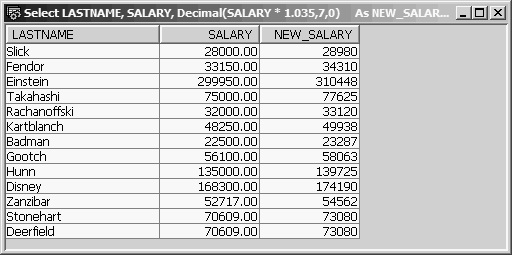

In addition, if the result were stored in a data file, its type would be packed decimal. For display purposes, the result is converted to readable numbers. The Decimal function works on the SALARY field of each record sent to the result table. With this function, the results of the preceding Select statement appear in Figure 13.20.

Figure 13.20: Virtual Column NEW_SALARY Formatted to Integer Using the Decimal Function

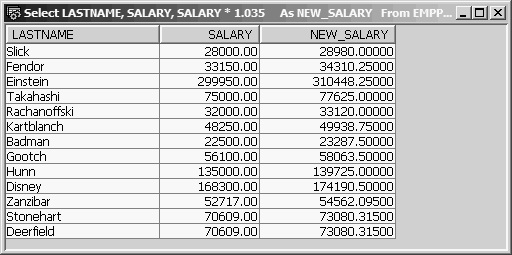

Without the Decimal function, the results look like those in Figure 13.21—that is, the NEW_SALARY column would have five decimal places.

Figure 13.21: Virtual Column NEW_SALARY with Decimal Precision Calculated by SQL

SQL calculated the precision and scale of field NEW_SALARY based on the arithmetic expression. Looking at the difference in these two figures, you can see how the scalar Decimal function has affected each row of the result table individually. A scalar function is invoked and returns a value for each result row.

In contrast, a column function returns only one value. It manipulates the column data of each row by adding to an accumulator, comparing for minimum or maximum value, and so on. The final result of this row-by-row data manipulation is not available until all selected rows have been processed. The final value is the function applied to the entire set of column values. For example, you can use the Sum column function to total all salaries:

Select Sum(SALARY)

From EMPPF

This statement instructs SQL to add the salary of each EMPPF record into an accumulator and to display the result after processing the last record. Note: This request is invalid (and nonsensical).

Select LASTNAME, Sum(SALARY)

From EMPPF

Because LASTNAME has a value for each record, it cannot be paired with Sum(SALARY), which derives a single value for the entire result table.

However, suppose we want the total salary for each department. SQL provides the Group By function to group records by a common value of a field and then perform the Sum operation on each group. The statement would be

Select DEPT, Sum(SALARY)

From EMPPF

Group By DEPT

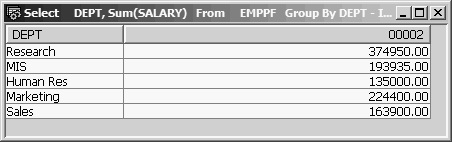

When you need a column function to act on a group of records, you must use a Group By clause to identify the grouping field or fields. The preceding statement instructs SQL to sort all EMPPF records by DEPT, then total the salary of the employees in each department, and then write one record for each department to the result table. It is important to understand that when you use Group By, the function works on the set of column values for each group, so one record per group is sent to the result table. Figure 13.22 shows the output from the statement.

Figure 13.22: Grouped Sum of Salary per Department

For example, say we want to list the last name, the employee number, the number of projects assigned, and the total hours spent on all projects for any employee who is working on two or fewer projects, or who has less than 50 total project hours to date. We also want to sort by last name.

This request calls for grouping project-member records by employee number and then selecting only those groups with no more than two projects or no more than 50 total hours. In addition, to get the last name, we need to join each group record with a matching record from the employee file, EMPPF, on employee number.

SQL provides a way to select or reject group records. The Having clause enables selection of group summary records in the same way that the Where clause enables selection of base table records. The syntax of the Having clause is

Having conditional-expression

Some constraints apply on the expression. Field names used in a Having expression must be specified in the Select field list. Function results can also be referenced in the Having expression and, except for Count(*), must also be identified in the Select field list. The Count(*) expression returns the number of rows in each group and can be referenced in a Having clause, even if it is not specified in the Select field list. You can also use subqueries in a Having clause.

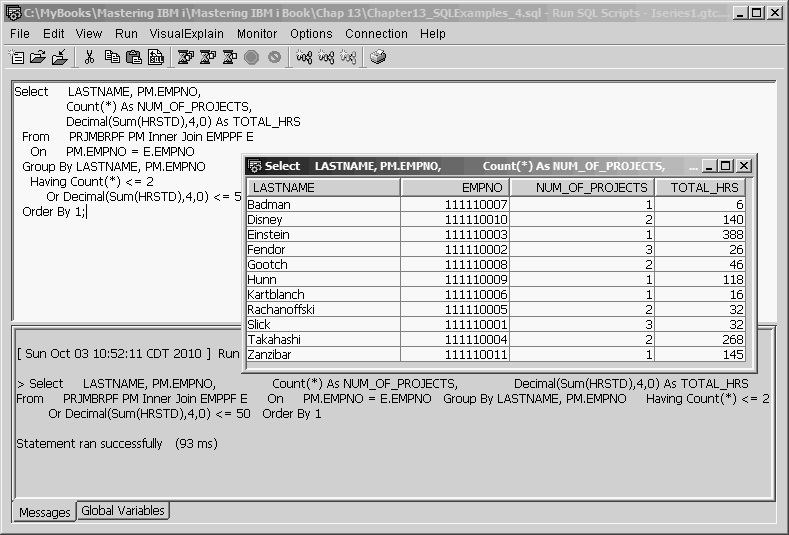

We can produce the necessary Underutilized Employee Report with the following statement:

Select LASTNAME, PM.EMPNO,

Count(*) As NUM_OF_PROJECTS,

Decimal(Sum(HRSTD),4,0) As TOTAL_HRS

From PRJMBRPF PM Inner Join EMPPF E

On PM.EMPNO = E.EMPNO

Group By LASTNAME, PM.EMPNO

Having Count(*) <= 2

Or Decimal(Sum(HRSTD),4,0) <= 50

Order By 1;

Assuming a referential constraint on PRJMBRPF, so that all employee-number values of any of its records must already exist in the parent file EMPPF, either an Inner Join or a Left Outer Join produces the same results using PRJMBRPF as the primary (left) file.

We must use both LASTNAME and EMPNO as the grouping fields. It is important to understand that only fields that will always have the same value for all records of a group can be used as grouping fields.

The Having clause limits the output to those group summary records whose count of projects is less than or equal to 2, or whose sum of all project hours is less than or equal to 50.

The Order By clause must also refer only to list items from the Select field list, but integer reference to the positional order of items of the Select field list is permitted. In the example, Order By 1 is equivalent to Order By LASTNAME. This feature is especially useful when the ordering column needs to be a function expression, to avoid having to rekey the expression. Figure 13.23 shows the output of the Underutilized Employee Report.

Figure 13.23: Underutilized Employee Report

Another example might help clarify when to use the Group By clause. For instance, let us say that we want to display the name and birth date of the oldest employee in the company.

Think of a date field as a numeric value with the high-order two digits being century, followed by year, month, and day. Therefore, the smaller the value of BIRTHDATE, the older the person. SQL’s Min function returns the smallest value in a table or group. You might be tempted to try

Select FIRSTNAME, LASTNAME, Min(BIRTHDATE)

From EMPPF

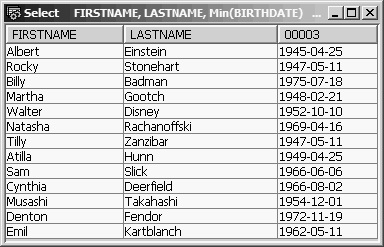

However, SQL would display the message “Column FIRSTNAME or function specified in SELECT list not valid” because you cannot combine column (field) names with a column function (Min) without using Group By. However, in this case, using Group By would be inappropriate because there are no groups of records in EMPPF with common values for the grouping columns FIRSTNAME and LASTNAME. What would result if you entered the following?

Select FIRSTNAME, LASTNAME, Min(BIRTHDATE)

From EMPPF

Group By FIRSTNAME, LASTNAME

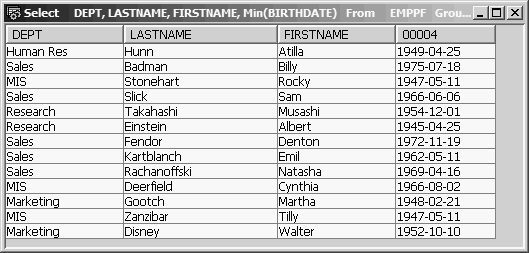

SQL would create “groups” of records for each unique set of values for FIRSTNAME and LASTNAME, or, in our database, one group for each employee. And because the column function applies to each group, each employee’s birth date would be the Min(BIRTHDATE) for the group (of one record). You would get a list of all employees’ names and birth dates (see Figure 13.24). Of course, if you had two John Smith employees, you would get only one result row showing the elder Smith’s birth date.

Figure 13.24: Group By FIRSTNAME, LASTNAME

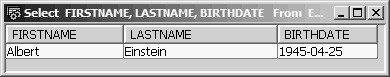

How can we attach a name to a birth date and be sure that it is the minimum birth date? Use a subquery! If we move the Min function to a subquery, we can compare each employee’s birth date against the Min(BIRTHDATE) value of the whole file and then select only the matching record.

Select FIRSTNAME, LASTNAME, BIRTHDATE

From EMPPF

Where BIRTHDATE = (Select Min(BIRTHDATE)

From EMPPF)

Instead of a list, the subquery—(Select Min(BIRTHDATE) from EMPPF)—returns a single value, the oldest person’s birth date, against which we are comparing each employee’s BIRTHDATE, as in Figure 13.25. The Min and Max functions always return only a single value, even if several selected rows share the same minimum or maximum value. If a company’s oldest employees were triplets born on the same day, Min(BIRTHDATE) would still return just one value—their common birthday.

Figure 13.25: Where BIRTHDATE = (Select Min(BIRTHDATE) From EMPPF)

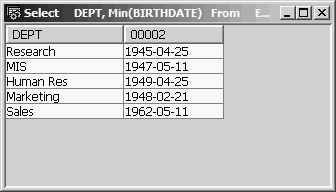

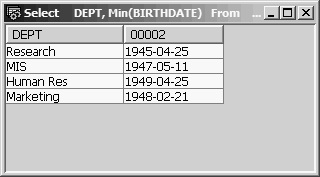

Now we might want to list the birth date of the oldest employee in each department. To satisfy this request, we can use DEPT as the single grouping field and write the Select statement as

Select DEPT, Min(BIRTHDATE)

From EMPPF

Group By DEPT

This Select statement would show each department and the birth date of its oldest employee (Figure 13.26). However, it would not tell us who the oldest employee is. When SQL requires you to name all Select list fields as grouping fields, there is no direct way to associate a department’s oldest birth date with a name or number.

Figure 13.26: Group By DEPT

The Select statement

Select DEPT, LASTNAME, FIRSTNAME, Min(BIRTHDATE)

From EMPPF

Group By DEPT, LASTNAME, FIRSTNAME

would take us right back to a list of all employees, as in Figure 13.27.

Figure 13.27: Group By DEPT, LASTNAME, FIRSTNAME

However, leaving the name fields out of the Group By clause but keeping them in the Select list, as in

Select DEPT, LASTNAME, FIRSTNAME, Min(BIRTHDATE)

From EMPPF

Group By DEPT

would be a syntax violation.

There are two ways to include the oldest employee’s name as well as birth date, and we will return to this problem a little later. But first we will look at another example of the use of the Having clause in a related request.

Say we want to list, for each department, the birth date of the oldest employee for each department who is at least 50 years old. (If the oldest employee of the Sales department is only 48, you would not want a Sales department record in the output.) We could easily satisfy this request by using the Having clause to limit the group summary records to those that meet the age criteria, as follows:

Select DEPT, Min(BIRTHDATE)

From EMPPF

Group By DEPT

Having Year(Current_Date – Min(BIRTHDATE)) >= 50

In this example, we are extracting the year from the date-arithmetic expression Current_Date – Min(BIRTHDATE) and comparing it with 50 (see Figure 13.28). If you think of a date as a point on a time line, then, in SQL, any two points can be compared and their difference expressed in years, months, weeks, or days.

Figure 13.28: Having Year(Current_Date - Min(BIRTHDATE)) >= 50

Another way to write the preceding Having clause is to use a labeled duration—that is, a date period expressed in one of the date units (e.g., years, months). Using labeled duration, our Having clause would be

Having Min(BIRTHDATE) + 50 years <= Current_Date

The + 50 years is the labeled duration. A labeled duration is always used to add or subtract some period of time to a known point of time, such as BIRTHDATE; and so it always starts with a plus or minus sign.

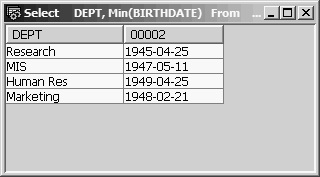

Returning to the question of how to include personal data with the birth date of each department’s oldest employee, first visualize the output of the earlier statement, as Figure 13.29 shows.

Select DEPT, Min(BIRTHDATE)

From EMPPF

Group By DEPT

Having Min(BIRTHDATE) + 50 years <= Current_Date

Figure 13.29: Having Min(BIRTHDATE) + 50 years <= Current_Date

If we could find a way to store this data, we could join it to EMPPF records based on the values of DEPT and BIRTHDATE in EMPPF and then extract any other employee data we needed from the joined record. In fact, the data is already stored in file EMPPF; we just need to build a kind of logical file over EMPPF to get at the data.

In the next article of this series, you will learn about SQL views (views are SQL’s version of logical files) and the SQL file-maintenance operations: Insert, Update, and Delete. Meanwhile, you may want to refer back to Part 1 and Part 2.

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn: Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online