IANARCW!

That's my disclaimer that states I am not an RPG compiler writer. I am also not one of the folks who designed ILE. Therefore, I cannot claim a fundamental understanding of all the nuances of the activation group concept. However, I can impart my own experience with activation groups, and I'll do so here.

What Are Activation Groups?

At the risk of being over-simplistic, activation groups act very much like mini-jobs. When an activation group ends, all the programs within that activation group get "cleaned up." I put the dreaded quotation marks around that term because cleaning things up means different things to different people. However, I think most people agree that at least part of cleaning up includes closing files and resetting variables to their initial state. In the case of RPG programs, cleanup also involves the initialization subroutine (*INZSR); if an RPG program is "cleaned up," we expect that the next time it is called its *INZSR will be invoked.

Pre-AG Days

Sometimes, the only way to understand today is to revisit yesterday. So let's return to the days of yore before activation groups, to what is now lovingly called the OPM, or Old Program Model. In the OPM world, programs called other programs all the time. One program simply calls another program, at which point the operating system finds the program dynamically and then automatically opens all files required by the second program, initializes its variables, and starts the program. The second program can read parameters passed from the first program, do its work (which may include updating those parameters that were passed), and then return to the previous program, which has been waiting patiently for the other program to finish. This synchronous call capability, in which one program acts as a subroutine for another program (with bidirectional parameters!), is unique in the programming world and very powerful.

In the early days, we used this feature at the application level to allow a customer inquiry program to invoke an order inquiry program. But as we got better at programming, we realized that we could encapsulate smaller pieces of business logic into callable programs, thus beginning the march toward modular code. But as the modules got smaller and we called them more often (for example, a pricing routine or an inventory adjustment), we ran into a new problem: When one program called another program over and over, the overhead of opening and closing the files every time was incurred. However, RPG allowed us an easy way to avoid this: By not turning on *INLR, we could effectively leave the files open. An interesting side effect was that all variables were also left in their current state, as were all file pointers. This made for some interesting programming techniques, such as simply reading forward or backward in a file to get records to fill a subfile; since your file pointer was already positioned, you didn't have to send keys back and forth to keep repositioning the file.

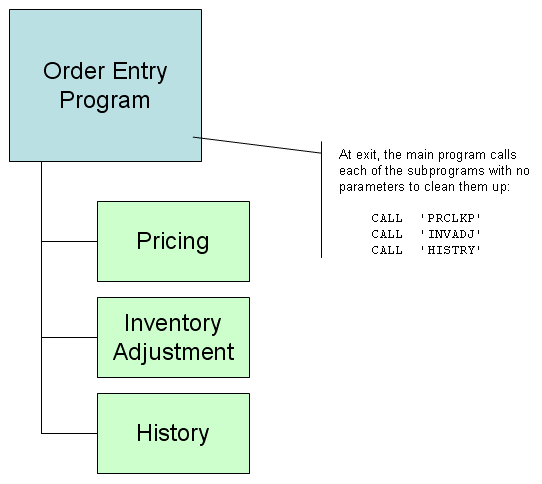

The problem was at cleanup time. You needed logic to clean up all of the "subprograms" you called. Otherwise, they would be in an indeterminate state for the next program. So you'd sometimes see mainline programs whose exit logic was a long list of calls to other programs to clean them up. (This also gave rise to the technique of passing no parameters to a subprogram; if the subprogram saw that no parameters were passed, it set the LR indicator on and returned, thus cleaning itself up.)

Figure 1: This is the brute force way of cleaning up subprograms. (Click images to enlarge.)

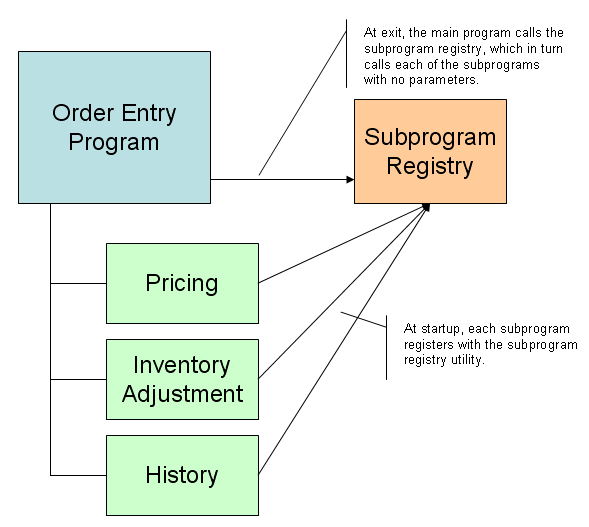

There was also the FREE opcode, but I never entirely trusted it. Not only that, but if you called a program that called another program, how could you be certain that your list of cleanup calls was complete? In the end, I wrote a utility program that allowed every subprogram to register itself with the utility. Then, when the main program was shutting down, it called the utility program with a shutdown opcode; this caused the utility to call each of the subprograms with no parameters to shut them down.

Figure 2: This is a slightly more sophisticated way of cleaning up subprograms.

Activation Groups to the Rescue!

The beauty of the activation group is that it removes the need for all that folderol. In fact, when I first realized how activation groups worked, I was actually upset for the tiniest moment because it meant I should throw away my registry utility, and I really hate throwing away perfectly good code. But that's what happens as a language or an OS matures (ask me someday about loading arrays from the highest entry backward before the introduction of the %SUBARR BIF).

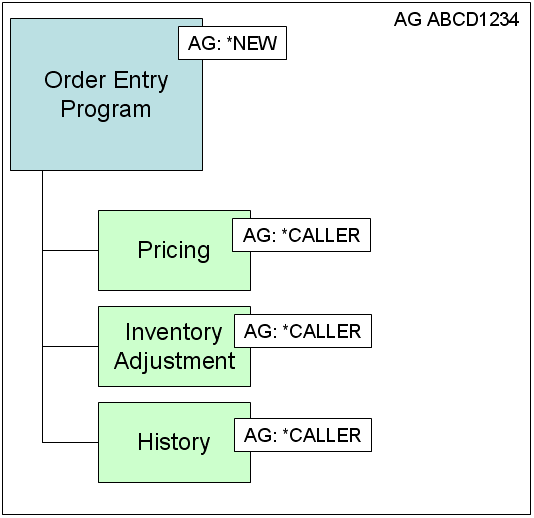

Anyway, here's the new picture:

Figure 3: Use a combination of *NEW and *CALLER to perform cleanup.

I've assigned the order entry program to an activation group of *NEW. This setting causes the operating system to create a new activation group (called ABCD1234 for the purposes of this illustration). By assigning each of the called programs to activation group *CALLER, I've caused them to inherit the activation group from the calling program, so they reside in the same ABCD1234 activation group.

Now, when the order entry program ends, since it was the "owner" of the ABCD1234 activation group, that activation group ends and all the programs in it are cleaned up. That's right, all the work I went through in Figures 1 and 2 is completely unnecessary in the brave new world of activation groups.

Note, however, that this only works in conjunction with the *NEW and *CALLER activation group settings. Named activation groups act differently in that they don't go away unless explicitly reclaimed using the RCLACTGRP command (or its API equivalent). Maybe I'll write another tip another day on using named activation groups. Also, be warned that the default activation group, which is used for OPM programs, throws several other twists into the architecture. This tip is specifically designed for applications written entirely in the ILE model.

I hope that, as you move to ILE, you'll have an opportunity to start modularizing your code if you haven't already. You can use this tip as one thing to make encapsulation much easier.

Joe Pluta is the founder and chief architect of Pluta Brothers Design, Inc. and has been extending the IBM midrange since the days of the IBM System/3. Joe uses WebSphere extensively, especially as the base for PSC/400, the only product that can move your legacy systems to the Web using simple green-screen commands. He has written several books including E-Deployment: The Fastest Path to the Web, Eclipse: Step by Step, and WDSC: Step by Step. Joe performs onsite mentoring and speaks at user groups around the country. You can reach him at

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online