Visual Basic (VB) is all grown up now. With the advent of .NET, VB has become aligned with the big players. It's capable of all those lofty concepts that C++ and Java programmers have been holding over its head for years. Indeed, the VB.NET programmer can now pull a chair up to the OOP table and commence throwing around terms like "base class constructor" and "System.Object."

But there's a price to pay for this status. Unlike previous reinventions of the VB programming language, conversion from VB6 to VB.NET is a whole different deal. In order to bring VB into the .NET fold, great changes were required, and the backward compatibility enjoyed in prior upgrades was necessarily sacrificed.

VB.NET's compiler generates Intermediate Language (IL) code, as do the other .NET programming languages, like C++.NET, C#, and J#. In fact, equivalent source code statements written in VB.NET and C++.NET will usually generate identical blocks of IL code. (See "Microsoft Computing: Microsoft's .NET Framework" for an introduction to the .NET application development system.)

The .NET framework is currently a Windows operating system add-on that provides the runtime support for .NET applications--those created with VB.NET, C++.NET, C#, or J#. In upcoming releases of the Windows operating system, you can expect the .NET framework to be integrated into the base functions of Windows.

Except for that word "basic" in its name, VB deserves all the respect due a full-blown OOP language. (Unfortunately and unfairly, VB may never acquire the same level of acceptance that other languages enjoy.)

Do I Have to Become "Object-Oriented" to Convert to VB.NET?

Do you have to learn the principles of OOP to use VB.NET? In a way, yes, you do. You'll find that a minimum degree of "object-orientedness" is required for even the most simple of VB.NET applications. For example, just to put a VB form in your .NET application requires your program to inherit the definition of a form from the System.Windows.Forms.Form class.

But becoming familiar with OOP concepts and practices is a good thing, especially in light of the direction the iSeries is taking toward Java. Perhaps gradual conversion of your VB6 applications to .NET is a practical and justifiable way to ease into a greater understanding of OOP.

Moving the Mechanisms out of the Closet

To accomplish this growth spurt, VB had to undergo considerable changes to its fundamental architecture. VB6 works something like the old RPG cycle. That is, an underlying "engine" provides the basic setup and processing mechanisms. Even a very simple thing like a VB6 command button receives considerable assistance from this unseen support mechanism. (Note: In VB.NET, a command button is just called a "button.")

In VB.NET, the enabling operations are out of the shadows. They're placed right in your source code, exposed to the world. Your forms and each of the components on them come into existence by virtue of plainly visible source code statements. The event handlers that respond to program and user actions are likewise evident.

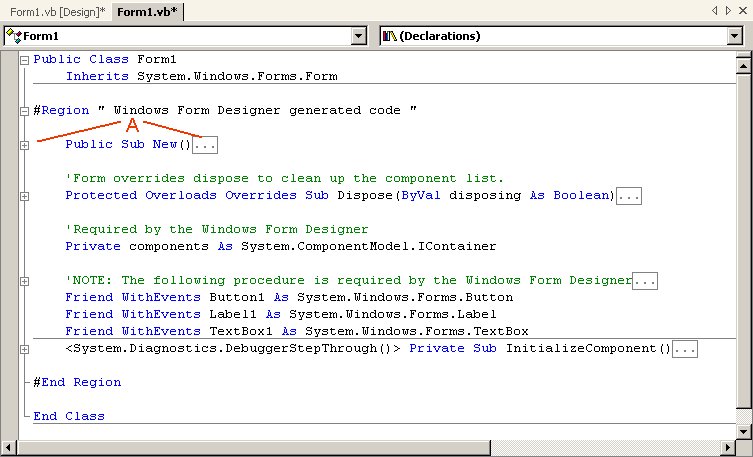

As an illustration, consider a very simple VB.NET form containing a label, a text box, and a command button (Figure 1).

Figure 1: This is the simplest of VB.NET forms. (Click images to enlarge.)

In VB6, with the creation of such a form, no real source code is generated. Not so in VB.NET. Just to display this humble screen requires the source code blocks shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: A VB.NET application generates these code sections for the form shown in Figure 1.

Note that the letter A points to a little plus sign (+) on the left of the display and a corresponding ellipsis (...). Each pairing of plus sign and ellipsis indicates there is a block of source code in there that the IDE is not showing. This is for convenience only; the code is readily available when the plus sign is clicked.

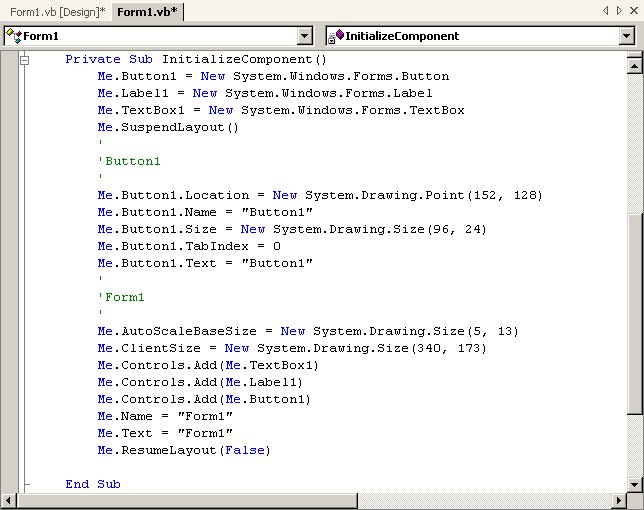

Figure 3 shows the expanded source code for the InitializeComponent() procedure. This is only a portion of the code that's required to put a few components on a form.

Figure 3: Here's a portion of the code that's generated when a VB.NET form is created.

Upon examination of the code in Figure 3, you'll see that we, as VB.NET programmers, are finally allowed to see what's going on behind the scenes. The components on the form aren't magically conjured as they were in VB6. Instead they're "instantiated" by us--that is, they're created explicitly in code from a pattern, called a "class." (See, isn't this fun? We're even starting to talk like OO programmers.)

Once the components (a.k.a. controls) are instantiated, we add them to the form's controls collection with the statement Me.Controls.Add(Me.TextBox1).

Converting from VB6 to VB.NET

That's not to say, however, that merely running your VB6 code through the conversion wizard will result in object-oriented design. It won't. What you'll get is equivalent code if possible, an error condition if not.

As I mentioned, a VB.NET conversion is nothing like VB conversions of the past. Conversion to VB.NET requires you to adopt the basic programming practices inherent in all .NET languages.

Each of the .NET languages acquires its functionality from the .NET library. At the heart of the library is System.Object. This is the core object from which all things .NET are derived.

Let's take, for example, the humble String and Integer variables. In VB6, a String or Integer variable is treated as a primitive data type. That is, it's just there--no properties or methods are associated with it. In VB.NET, these data types are objects. That is, they inherit their basic existence and properties from the mother of all objects: System. Therefore, a shift in thinking is in order.

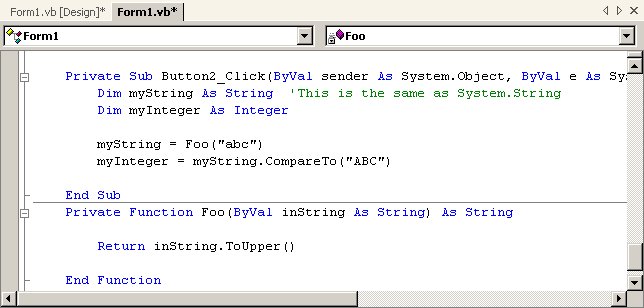

In figure 4, a function--Foo--is defined. This function accepts a String as a parameter and converts it to uppercase with the new VB.NET String.ToUpper() method. (Yes, the .NET String object type has methods--and properties, too!) Then, VB.NET's new form of the Return statement sends the String back to the calling procedure.

Figure 4: The .NET languages include String and Integer objects.

Notice also this statement: MyInteger = myString.CompareTo("ABC"). This is an example of how objects are often compared to one another in .NET, by invoking the CompareTo method of the object. CompareTo returns a positive, negative, or zero integer, which reflects the result of the comparison (high, low, or equal). This way of doing things is typical of the Java and C# environments.

This is not to suggest that your old VB6 coding friends have forsaken you altogether. Faithful companions such as UCase("abc") are still available in VB.NET and behave as they did in VB6. On the other hand, other VB6 statements have lost their role and will have to be recast as .NET players. For example, in VB.NET, the statement Clipboard.GetText() is no longer valid. It must be replaced as shown in this example:

' Not valid under VB.NET:

sWork = Clipboard.GetText()

-----------------------------

' Must be replaced with:

Dim iData As IDataObject

. . .

iData = Clipboard.GetDataObject()

sWork = CType(iData.GetData(DataFormats.Text), String)

In a situation such as this, the converted code is so dissimilar to the original that the utility Microsoft provided to perform most of the conversion effort could not cope.

The VB.NET Upgrade Wizard

To assist with the large migration leap from VB6 to VB.NET, Visual Studio.NET supplies a conversion utility called the Upgrade Wizard. The wizard accepts a VB6 project file as input and then creates the corresponding VB.NET source code statements, as best it can. Things that the wizard cannot convert have to be examined and migrated manually.

To run the Upgrade Wizard, start the Visual Studio .NET IDE. From the File menu, select Open and then Convert.... Select Visual Basic .NET Upgrade Wizard. On subsequent screens, you'll be prompted for the path and name of the existing VB6 project file as well as the location where the wizard is to write the new VB.NET source code.

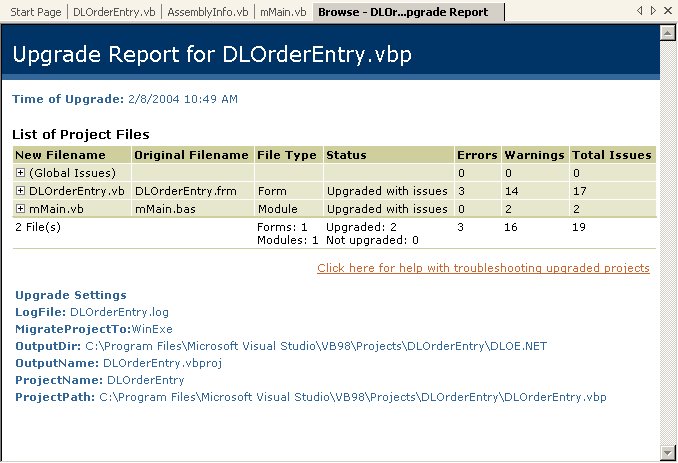

The wizard will churn for a while, and then you can display the results of the conversion effort. They are logged in the file _UpgradeReport.htm, as in the simple example in Figure 5.

Figure 5: When you use the Wizard to convert from VB6 to VB.NET, the results will be displayed.

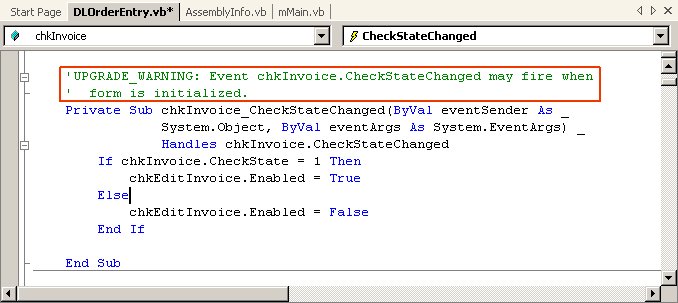

Any portion of the source code that could not be converted will be flagged as an Upgrade_Issue or an Upgrade_Warning, as shown in Figure 6, and an entry will be placed in the IDE's task list.

Figure 6: The wizard generates a warning message for source code that won't convert.

The degree of manual conversion required for an application can be quite large and will probably correspond to the size of the application itself. The changes to the code will likely be repetitive in nature, so you may be doing the same thing several times in a large program.

The Wizard Can Be a Valuable Tutor

Observing the changes invoked by the VB6-to-.NET conversion wizard is a great way of becoming familiar with the way things are done in .NET. If you are an RPG programmer, you are probably familiar with the iSeries CVTRPGSRC command, which converts RPG III to RPG IV. This command can be a great teacher of RPG IV. Similarly, in addition to being a useful utility that creates VB.NET source from VB6 source, the wizard is a VB.NET tutorial. When a given VB.NET syntax is unclear, a VB.NET programmer can create the familiar VB6 statement and run the source code through the wizard to discover the answer.

Be aware, however, that the Upgrade Wizard sometimes fails to convert what seems to be an obvious change. In these cases, there is usually a pretty good reason for the omission, so you'll have to do a little research to see what your alternatives are.

The Decision to Convert to VB.NET

Deciding when and if to convert your VB applications is not so easy this time. Migration to VB.NET requires more know-how now than in conversions past. At the very least, the effort is going to entail some research to determine how a given chunk of code or a given custom control can be replicated or replaced in VB.NET. It's also likely that you'll need a higher degree of familiarity with the OOP way of doing things. That means there may be some educational factors to consider as well.

At the other end of the spectrum, one may be tempted to completely rewrite a given VB6 application as native VB.NET. This may well be the wisest course, but it brings to mind another point: If you're going to learn all about the .NET development environment and something about OOP and rewrite your application, maybe there's a better choice than VB. Maybe rewriting an application in VB.NET doesn't make sense when there are compelling advantages in moving to the Java, C#, or even C++ .NET platforms (such advantages include portability and an elevated level of respect for your applications).

If your applications are commercial packages, you really have no choice but to migrate to .NET in one language or another. If you don't, eventually your applications will be perceived as being of the "old model," where such annoying things as the VB runtime support module were necessary.

The threshold between the last version of VB and the new version is quite high this time, but there really wasn't much that could be done to help it. If VB is going to move forward and live on, it must be part of the .NET family. Otherwise, it would wither into an obsolete language, and you would have to convert to something else anyway.

The MSDN Web site offers additional information regarding VB6 to .NET migration as well as an overview of Visual Studio .NET and the .NET framework.

Chris Peters has 26 years of experience in the IBM midrange and PC platforms. Chris is president of Evergreen Interactive Systems, a software development firm and creators of the iSeries Report Downloader. Chris is the author of The OS/400 and Microsoft Office 2000 Integration Handbook, The AS/400 TCP/IP Handbook, AS/400 Client/Server Programming with Visual Basic, and Peer Networking on the AS/400 (MC Press). He is also a nationally recognized seminar instructor. Chris can be reached at

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online