Like many of you, I have spent my professional programming career looking for ways IT can give my company an edge over the competition. I have seen firsthand the benefits of cross-platform object-oriented programming. Unfortunately, I have experienced problems with scalability, security, system complexity, and data integrity. I would like to find a system that is easy to use, has an integrated database, can be accessed from the Internet, and supports a powerful object-oriented language. As the ad says, “...that would change everything.” With Java servlets, JavaServer Pages (JSPs), IBM WebSphere, and the AS/400, perhaps there is finally a winning combination.

Web Application Servers

When Java first came on the scene, it seemed a perfect fit for the AS/400. At last, maybe there was a worthy successor to RPG. But would Java “play nice” on the AS/400? Could I leverage my company’s investment in several million lines of RPG code and a database developed over a period of years? Could I draw a line in the sand, stop developing in RPG, and switch over to Java without skipping a beat? My initial experiences with Java answered those questions with a firm no, but, after the completion of my most recent project, the answer is now maybe.

The New Application Architecture

At this time, you have several practical ways to run Java programs on an AS/400. You can run them as batch programs (OK). You can run them interactively from a command prompt using Run Java (RUNJVA) (slow). You can run them within the Qshell environment (slow). They can be called from RPG or CL programs (if you like pain). Or you can run them from a Web application server, such as WebSphere (now we’re talking). WebSphere provides a Web-enabled environment that lets you focus on the applications and not the supporting infrastructure. You don’t want to spend time thinking about managing a user’s connection to your system, nor do you want to manage database connections. In the green- screen world, you didn’t worry about this background stuff. When was the last time you, as a programmer, worried about how the user obtained a sign-on screen? You need to

concentrate on writing the application to solve business problems, and the operating environment should handle all the background stuff.

One of the last remaining sore points I had against Java was that the code for the user interface was often embedded within the business logic. In the GUI world, this can be incredibly time-consuming for the programmer. In the RPG world, you are used to creating a display file with SDA and then being free to focus on the business logic in the RPG code. The addition of JSPs brings this same freedom to the Java servlet world. JSPs handle the formatting of data for the user interface, and Java servlets handle the management of data. The combined use of JSP and servlets allows you to separate the business and presentation logic.

Figure 1 shows the basic configuration I recommend. A typical interactive session with a user is as follows:

1. A user starts up his favorite Web browser.

2. The browser’s URL references an AS/400-based Web site.

3. The AS/400’s HTTP server services the user’s request by sending an initial HTML Web page to the browser (the initial page is analogous to a 5250 menu).

4. The user clicks on a menu option of the Web page.

5. The browser sends the user’s request to the AS/400-based site powered by WebSphere (or some other Web application server that supports servlets).

6. The Web application server recognizes a request to run a servlet

(like a green-screen menu trying to run an RPG program). The Web application server starts up the servlet, creating a unique environment for this session, and passes to the servlet the user’s menu option request.

7. The Java servlet, as an application controller, responds to the user’s request by accessing the database (either with direct database calls, RPG/legacy program calls, or Enterprise JavaBeans). The servlet then crunches the retrieved data with its business logic, and, finally, the servlet assembles that crunched data into the information required to respond to the user.

8. The servlet puts all the acquired data into a JavaBean object (often called view beans or smart parameters) and forwards control to a JSP (kind of like an EXFMT in an RPG program).

9. The JSP formats the data contained in the passed view bean into a Web page.

10. WebSphere passes the dynamically constructed Web page back to the browser so the user can view the response.

Not too bad, huh? This process is similar to that of your RPG programs and 5250 display files. You only had to code four pieces: the initial HTML page, to contain a menu; the Java servlet, which contains the business logic; the JavaBean, which holds the display data; and the JSP, which generates the user interface. (See the sidebar, “HTML, Servlets, JSPs, and JavaBeans: A Code Example,” to see how information is processed in this new application architecture.) One thing I can’t convey in the simple diagram shown in Figure 1 is that, in real life, this setup, without adequate performance tuning, runs like a dog. The 1 to 2 second response time you are used to in RPG may turn into several minutes with an improperly tuned Java application. My article, “A Programmer’s Notebook: Making Servlets Run Faster,” on page 78 lists a number of tips that you can use to make your server-side applications as fast as your legacy RPG applications.

HTML, Servlets, JSPs, and JavaBeans: A Code Example

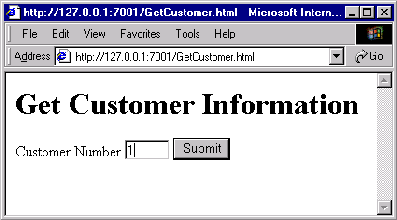

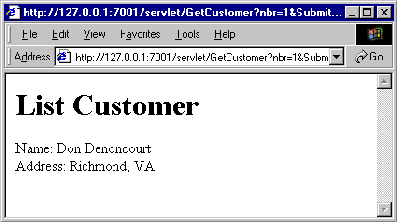

At first glance, the new application architecture that Alex Garrison used to transform his company’s IT applications sounds fairly complex. But, as Alex explains, “This process is similar to that of your RPG programs and 5250 display files.” I’m going to prove Alex’s statement with the retrieve customer information example shown in Figure A1 and Figure A2.

Figure A3 shows the HTML code for Figure A1; it simply prompts the user for a customer number. The most important line of the HTML code is this form tag:

The Action option of the form tag qualifies a Java servlet called GetCustomer as the server-side application that is to handle the user request. When the user clicks the Submit button, your Web application server will invoke the GetCustomer program shown in Figure A4. The init function (or method in object-oriented parlance) of the GetCustomer class sets up a connection to DB2/400, but it’s the doGet method that does the work of responding to the user’s HTML-based request. The doGet method retrieves the customer number with the getParameter method, uses that number to create a Customer JavaBean (by invoking its getCustomer method that uses SQL to retrieve the customer data), sets that JavaBean as an attribute/parameter of the user request, and passes control to a JavaServer Page (JSP).

The Customer JavaBean, shown in Figure A5, is an example of what I call a “smart parameter” because essentially it is simply a data structure with functions that is passed as a parameter to a JSP. The *ENTRY *PLIST of JSP, shown in Figure A6, that references the smart parameter is the jsp:useBean tag. The JSP retrieves values out of the JavaBean with the getName and getAddress methods. Note that Java code of the JSP is nested between pairs of <% and %>. Otherwise, the JSP contains standard HTML code.

—Don Denoncourt

Don Denoncourt is a senior technical editor for Midrange Computing. Don has six years of object-oriented design and programming experience and now considers himself to be a “Java evangelist.” He can be reached at

.

Figure A1: HTML files are used for initial prompting.

Figure A2: HTML is dynamically generated by a JavaServer Page using data from a JavaBean.

Get Customer Information

import java.io.*;

import javax.servlet.*;

import javax.servlet.http.*;

import java.sql.*;

import denoncourt.*;

public class GetCustomer extends HttpServlet

{

Connection con;

public void init() throws ServletException {

try {

Class.forName("com.ibm.db2.jdbc.app.DB2Driver");

} catch( ClassNotFoundException e) {System.out.println(e);}

try {

con = DriverManager.getConnection("jdbc:db2:*local");

} catch (SQLException e) { System.out.println(e); }

}

public void doGet(HttpServletRequest req, HttpServletResponse resp)

throws ServletException, IOException {

String number = req.getParameter("nbr");

Customer cust = getCustomer(number);

req.setAttribute("Customer", cust);

getServletConfig().getServletContext().

getRequestDispatcher("/listCustomer.jsp").forward(req, resp);

}

Customer getCustomer (String number) {

Customer cust = null;

try {

Statement sql = con.createStatement();

ResultSet rs =

sql.executeQuery("select nbr, name, addr from custmast " +

"where nbr = " + number);

rs.next();

cust = new Customer (

rs.getInt(1), rs.getString(2), rs.getString(3));

} catch (SQLException e) { System.out.println(e);}

return cust;

}

}

Figure A4: A Java servlet handles the user’s request by retrieving data from the database, stuffing that data into a JavaBean, and forwarding control to a JSP.

package denoncourt;

public class Customer {

private int number = 0;

private String name = "default name";

private String address = "default address";

public Customer() {}

public Customer (int number, String name, String address) {

this.number = number;

this.name = name;

this.address = address;

}

public String getName() {return name;}

public String getAddress() {return address;}

}

Figure A5: A JavaBean contains the information obtained by the Java servlet.

class="denoncourt.Customer" />List Customer

Name:

<%= Customer.getName()%>

Address:Figure A6: A JSP formats the information contained in a JavaBean by using a combination of HTML and Java syntax.

<%= Customer.getAddress()%>

JSPs Servlets Smart Parameters/View Beans

Input Handled by Servlet Build HTML from View Bean Info

Application Controllers DB2 Access

HTML

Generate User Interface

Forward

Control to JSP

Create View Beans

Figure 1: The new application architecture uses HTML, Java servlets, JavaBeans, and JavaServer Pages.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online