Service-Oriented Architecture is more than a buzzword.

I've been writing about Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) for some time now. I did a complete review of the state of the technology in an article I wrote back in November of 2004. In that article, I commented that SOA is really the latest version of client/server technology, except that it had already been saddled with a couple of pieces of ungainly baggage, namely Simple Object Access Protocol (SOAP) and Universal Description, Discovery, and Integration (UDDI). In the article, I noted that UDDI was useless and that SOAP had a couple of contenders, and I predicted that SOA would evolve away from reliance on those technologies.

Here we are three and a half years later, and UDDI is but a troubling memory, while SOAP is just one of the transport protocols, with Representational State Transfer (REST) with JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) being used as a lightweight replacement for XML. In my opinion, that brings SOA back into the game as a full contender for application architecture. My concern in the original architecture was that SOA was tied too closely to bad architecture, much like Enterprise Java Beans (EJB). But EJB has evolved (we'll be reviewing the new EJB3 specifications in a little more detail in an upcoming article) and so has SOA, and that means it's worth another look.

Please note that I'm not in any way embracing any of the more esoteric terms that tend to get associated with SOA. The simple SOA implementations that I'm concerned with don't require Federated Databases or Enterprise Service Buses (ESBs). I'm not dismissing those technologies; I just don't see the need for them in many applications and certainly not in the context of this article.

Multi-Tiered Architectures

Which bring me to the point of this article, specifically how SOA fits into today's multi-tiered architectures. But to do that, we have to take a little trip down memory lane, although I'll try to keep it brief.

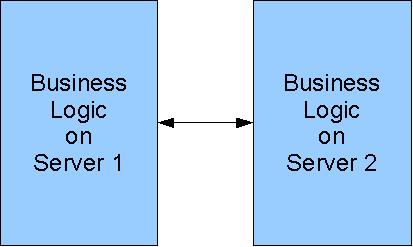

Figure 1: This is a standard peer-to-peer (P2P) architecture...

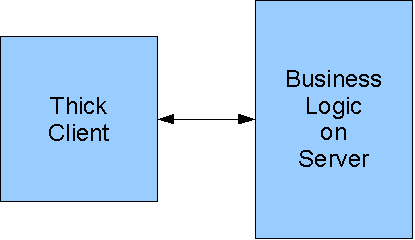

Figure 2: ...while this is the thick-client design.

Let's take a look at a couple of the very simple versions. You can see a peer-to-peer (P2P) architecture in Figure 1 and the thick-client design in Figure 2. Both of these are simple, two-tiered designs but with widely divergent goals. The first is typically used for passing data between two servers, along the lines of EDI transactions. Dozens of variations probably exist, ranging from true EDI to simply sending flat files from one machine to another. The second is more about presenting data to end users and/or letting them input data back to the server. The thick client, especially in these earliest systems, was most typically a PC workstation of some type.

In either of these designs, the vast majority of implementations, especially in the '80s and '90s, was done via some sort of custom protocol between the machines. They might use a standard transport mechanism (do any of my dinosaur brethren remember bisynchronous communications?), but the format of the data passed between tiers was usually proprietary and custom. I've designed dozens of these protocols over the years; that design was often a significant part of any multi-tiered project.

Without going into a long sidetrack on this issue, let me point out that the design in Figure 1 has remained essentially unchanged over the years. When two machines talk to one another, there are no issues of user interface; it's usually just a matter of getting data from one place to another and then reporting success or failure. And while I'd love to talk about multi-casting and service buses, that's outside the scope of today's discussion.

Instead, I'd like to move on to the aspects where change has really occurred in the last several years: the user interface.

User Interface Strategies

The original user interface approach was the thick client of Figure 2. Again, let's not spend a lot of time on the past, but it's important to understand that one of the biggest issues with thick client was that every time the client changed (whether it was a change in the operating system or a change in the hardware or any of a myriad of other things), then the client-side code had to change. It meant keeping different versions for different clients and pushing out changes to all the different machines; in general, thick-client code was a maintenance nightmare.

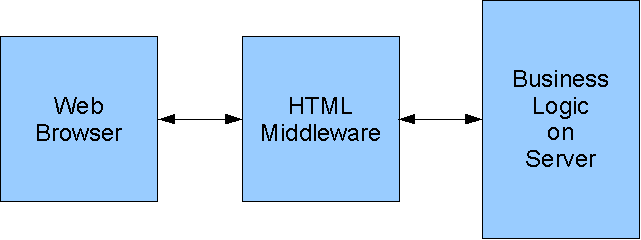

Figure 3: This is the browser approach.

Then came the World Wide Web, HTML, and the Web browser. Browsers made it easy to write code that could talk to most clients, because you simply used HTML, and most browsers could handle it. I'm simplifying and avoiding the Browser Wars and all that stuff, but the issue is pretty simple: In this architecture, there still isn't much of a need for SOA, because the real inter-machine communication was done via HTML. But that was about to change.

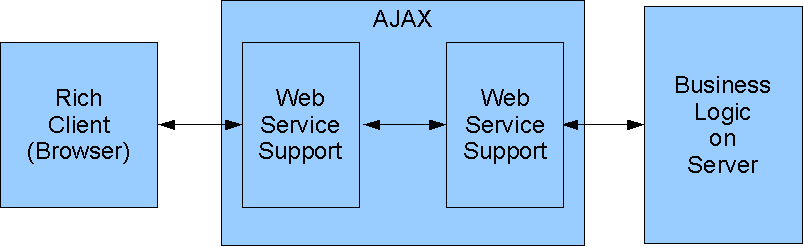

Figure 4: The rich client brought services to the fore.

What happened was the advent of JavaScript and the concept of the rich client. Instead of just sending data down to the browser in the form of HTML, the browser began to be treated as a virtual machine, and JavaScript became the standard language of rich-client applications. An entire program would be sent down to the browser, and that program would act like the thick clients of old. However, since JavaScript was relatively standardized and ran inside the relatively consistent browser model, a lot of the distribution issues went away. Instead, what came out was the idea of sending small bits of data between the browser and the business logic server, using the idea of a Web service.

In simplest terms, a Web service is a way to send a request to a business logic server and get a response back. With AJAX, that service could easily be sent from a browser to an HTTP server on the host, which would then in turn call the business logic. The Web services technology was pretty stabilized and, although it could be rather inefficient, it did allow developers to write to a standard and no longer have to worry about the protocol between the UI and the business logic. Instead, the Web service support on the server side was in charge of calling the business logic.

The User Interface Side Barrels Ahead

If you've been following any of the rich-client technology stuff (also sometimes called Web 2.0), you've probably been amazed. If you'd like to see a great example of an application, take a look at the scheduler demonstration that Chris Laffra of IBM and I wrote for the IBM Rational Software Development Conference coming up in June. You can see it by going to http://www.laffra.com/ and then clicking on one of the demo links; you'll see two links because the application is deployed both on a public server in a Linux environment and on a WebSphere server here in my office.

Our application is actually very simple; others are incredible. Dashboards that provide instant graphical representation of real-time status information make up one category; another includes fully interactive business graphics with drill-down capabilities. Google provides a broad spectrum of callable APIs that provide everything from basic widgets, to powerful Google maps, to the new generation of Web applications.

But because of this, it became more and more important to be able to go back to the server for small pieces of data in response to user events rather than completely rewriting the screen. This was the underlying requirement behind the entire AJAX concept. So let's move on to how AJAX works and why it provides a concrete foundation that allows the rather ephemeral concept of SOA to take on substance.

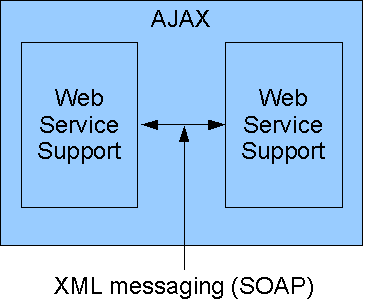

Figure 5: In the original AJAX, XML and SOAP were used for messaging.

Figure 5 shows a closeup of the messaging between the two tiers of the application. This original design used Web services as the transport layer, and XML provided the protocol. More specifically, the SOAP protocol was used, which provided the benefit of a high degree of standardization at the cost of a somewhat inefficient mechanism. Even the most basic SOAP envelope added 500 bytes to every message. While this is inconsequential to a message measured in megabytes, it can quickly overwhelm an interface that responds to individual key strokes or even simple mouse movements. A leaner communication mechanism was needed.

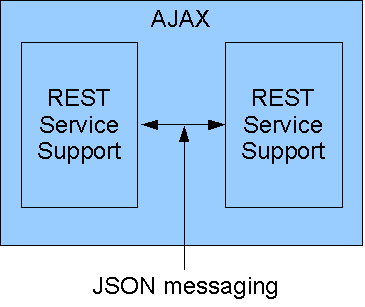

Figure 6: A more efficient method is to use pure REST, with JSON messaging.

Figure 6, then, shows the JSON approach. JSON uses a much simpler syntax, so it can provide a much cleaner interface. Here is a simple example of XML versus JSON:

XML

<ToDo>

<Task>Weed Garden</Task>

<Priority>3</Priority>

<Hours>1.5</Hours>

</ToDo>

JSON

{ "Task" :"Weed Garden", "Priority" : 3, "Hours" : 1.5 }

Note, though, that with enough work the XML can be shortened considerably:

XML 2

<Todo "Task"="Weed Garden" "Priority"=3 "Hours"=1.5 />

By using lots of attributes, you can reduce XML quite a bit, although most XML transmissions I've seen look more like the first XML layout rather than the second. And no amount of cleanup of the XML can get around the fluff that's put in by SOAP.

However, the point is this: By using a standard, no matter how inefficient, you remove the part of your design and coding that used to be committed to creating a new protocol. Thus, you remove a large part of the programming effort (especially on sophisticated applications where those protocols tend to be complex and hard to debug).

By removing the hurdle of communication, you can concentrate instead on the application design itself. And that's what I mean when I talk about providing a solid foundation for SOA development.

The Future of SOA

This is really the big question: Where is SOA headed? To me, SOA is going to become a sort of umbrella term for loosely coupled application tiers. I see business logic becoming more focused on providing a service than identifying pixel positions for data, while UI components focus on the user experience and rely entirely on the back-end servers to provide the logic.

This is a wonderful world for RPG programmers, by the way. They can focus on the wonderful capabilities of the RPG language and the DB2 database, without having to try to shoehorn their world into 24 rows of 80 characters (or 25x132, but you get my drift). Instead, they will provide message-based services, adding line items or shipping orders or posting credits. No longer constrained by the user interface, programs can become more powerful than ever before.

No longer do they have to try to figure out the appropriate combination of PUTOVR, OVRATR, and ASSUME to get a popup window to work. Nor do they have to learn the intricacies of HTML, JavaScript, and CSS; the UI developer will do that. Of course, if RPG programmers want to become UI designers, nothing is stopping them. But the point is that they don't have to.

Modernizing your applications becomes a matter of replacing display files with data structures, and the rich client can take care of the details. The really nice thing about that is that whenever a new device comes along, nothing changes in the business logic. Important RPG programming time is no longer spent on cursor position (or even worse, formatting HTML). Instead, RPG programmers code business logic, and life is good.

It's not the easiest thing in the world, perhaps, especially if you've spent as many years as I have: writing monolithic RPG order-entry programs. But even 20 years ago, we were starting to consider writing small modules: pieces of logic that were called by the larger programs. This is only a continuation of that trend, toward business logic with no user interface.

OK, Tell Us About EGL

You knew I'd get to EGL eventually, didn't you?

Well, only a little bit, I promise. The thing that really makes EGL special in this brave new world is that it works or will work all along the SOA spectrum, making things easy right up to the point where your existing RPG skills take over.

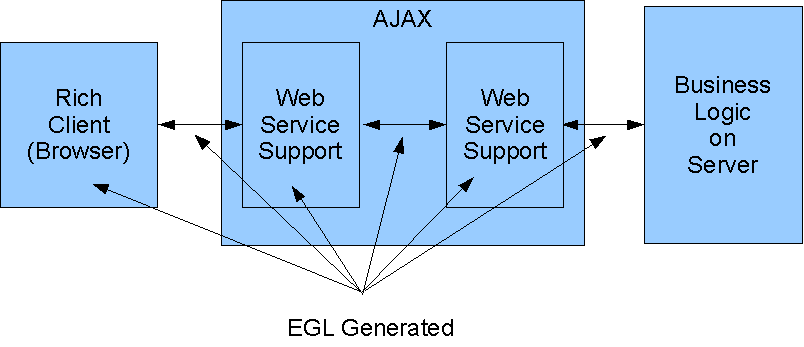

Figure 7: This is where EGL plays in the SOA spectrum.

Take a look at Figure 7. You can see three primary components: the rich client, the REST service, and the business logic. In reality, though, there are a number of smaller components, including the client and server side of the REST service as well as the interactions at each step of the way. In current development, even if you use a Web service, you will still have to:

- Convert the client data on the browser to am XML document and...

- Send it to the client side of the Web service that will...

- Wrap the XML in a SOAP wrapper and...

- Send it to the server side of the Web service, which will...

- Parse the data on the server side into the server's internal format...

- And finally send it to the business logic.

Other than the WSDL document that defines the layout of the XML inside the SOAP wrapper, there is no real standardization at each step of the process. No standardized data structure exists on both sides of the transaction.

With EGL, the Record part does this. In the case of the to-do list example, I could create an EGL record:

ToDo Record type BasicRecord

Task string;

Priority int;

Hours decimal (3,1);

end

Rich-client EGL developers can use that record on the client side to develop a rich-client EGL application. They can then specify that the record is part of a Web service call. On the server side, I can write a Service part in EGL, write a function using that same record type, and then expose the function as a Web service. EGL will take care of converting the record to and from XML as needed to transport the data between the client and the server. Finally, I can pass that record to an RPG program as a data structure, and the RPG program can use it to perform business logic.

The same metadata is used at every point in the process. The only thing that EGL doesn't do for me is write the RPG program, and that's OK, because that's what RPG programmers should be getting paid to do! Write business logic, not pixel positions! And EGL is awfully easy to learn. It won't take forever and a day to put a pretty front-end on your existing logic.

I think we're at a position now where we can truly use the philosophy of SOA to begin developing code in multiple tiers. It will take a little bit of revamping, especially of the more convoluted old legacy applications, but if you do it carefully, I think you can then use some of the new UI technologies to quickly show some return on your investment, which buys you time to make more changes to the base code, which in turn lets you create even more powerful applications. And before you know it, you'll be starting to add brand new business logic in response to user requirements, rather than patching old monoliths just to keep them rumbling along.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online