In “The First Degree of Separation,” Kevin Vandever reviews the various messaging technologies, while my article “Opening Up Your Options” shows you how to use messaging to separate the user interface (UI) from the business logic in your legacy systems. User interface separation is an essential but essentially invisible step, since, to the user, you still have the same old green-screen. However, by implementing that separation, you pave the way for revitalization. Separation is the footwork, and revitalization is the payoff.

Revitalization is the shortest distance between green-screens and GUIs. By using the techniques I outline in this article, you’ll be putting a graphical face on your existing applications in no time. Revitalization allows green-screens, PC-based graphical interfaces, and browsers to all coexist, sharing the same host code. It does so by taking advantage of the server/client architecture you enable during user interface separation.

Server/Client Architecture

Revitalization relies entirely on the server/client architecture. Let’s take a closer look at that architecture. To do that, we need to define some terms:

• User interface. This is the portion of the program that actually communicates with the user. Its sole purpose is to display data and retrieve information from the user.

• Application logic. This section of the code decides which portion of the business logic to execute and then which screen to display based on user actions.

• Business logic. This code performs discrete functions on specific business entities, such as retrieving a list of customers or updating an order.

These are wonderful categories, but they don’t map well to existing monolithic applications. Much of today’s legacy code (especially the older code) does not lend itself to reengineering. Chunks of business logic are intertwined with pieces of application control and tangled up with bits of UI code. It’s nearly impossible to separate the different strands. That’s what makes transforming legacy code into true object-oriented client/server code so difficult; it’s difficult to decide which strands belong together.

The server/client technique allows you to delay that difficult process while still putting a graphical interface together. Unlike separating the different logic threads, it is relatively simple to find the point where the monolithic program and the UI meet. All

interactive programs use a display file, and in the case of RPG, only a few simple op codes communicate with that display file: EXFMT, WRITE, READ, READC, and UPDAT. After the UI is separated, the idea behind the server/client architecture is to replace those op codes with messages using the protocol outlined in my article “Opening Up Your Options.”

Application/Business Logic

With the server/client approach, you don’t have to worry about separating the application and business logic. You can defer that task until after your UI work is done. Instead, you can focus on your UI deployment options. The UI becomes the server; it processes requests from and responses to the original legacy code. These requests and responses replace the display file I/O operations. A program modified this way can be termed an application client.

Server/client technology can support any sort of user interface, from green-screens to highly integrated desktop thick clients. The primary application and business logic is still in the original high-level language of the legacy code and, in fact, looks very much like the original program. If you are using a third-party vendor’s software, you can retrofit any vendor PTFs with no modifications as long as they don’t affect the actual display file. Changes that do affect the display file would require regeneration of the UI servers as well.

Green-screen UI

One of the benefits of this approach is that you can still have a green-screen interface with very little work. Creating a green-screen UI allows you to gradually replace your green- screens with GUIs and still gives you the option of having dumb terminals where they make sense, such as on the shop floor or in other PC-hostile environments.

The key to the green-screen deployment option is the display program. This program is simply an extension of the original display file. It receives output requests from the server and relays them without modification to the old display file. For input requests, the data received from the I/O operation is simply stored in the message and sent back as a response.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the green-screen implementation is that, in many cases, both programs—the application client and the UI server—can be programmatically generated from the existing monolithic program. The strict columnar structure of RPG III, in particular, lends itself well to finding and replacing specific op codes with other op codes. You can write a program to analyze an application program’s source code, remove its display file, and replace all I/O op codes with calls to a messaging program. For example, every place the original program had an EXFMT op code would be replaced by an EXSR to a subroutine that calls the message API. The utility can just as easily generate the display program automatically based on the formats and operations required. In the previous example, if the only I/O op code in the original program were an EXFMT, the display program would handle a single message type, which would trigger an EXFMT. Time spent developing this methodology allows you to spend more creative energy on the graphical interface options.

JSP/Servlet UI

A variety of thin-client options is available, and I could spend an entire article simply discussing the advantages and disadvantages of the different approaches. In the broadest sense, a thin client is one in which no host-specific program resident exists on the workstation. Any host-specific code is downloaded at runtime. The primary example of just such a distributed program architecture is Java applets—the applet is stored on the host until the client requests it, at which point it is transmitted over the network connection and run immediately on the client. This approach is too dependent on application-specific factors for me to do it justice in this space. However, many of today’s thin-client strategies avoid sending any program code at all. Instead, these architectures have programs that run

on the host and output industry-standard HTML that a generic Web browser then interprets. Of the HTML-based options, I believe that the JavaServer Pages (JSP)/servlet architecture has the most promise. There are a number of reasons, the most important being that you can easily use JSP/servlet technology as a first step to some of the more object- oriented approaches. (I touch on this subject at the conclusion of this article.)

JSP are an extension of HTML, with special tags that allow direct access to JavaBeans. This is different from JavaScript, which embeds Java-like code inside the HTML; JSP provide a separation between the HTML designer and the programmer by defining a contract between the two. Each JavaBean is, in effect, a self-contained API that can insert data into the HTML page. My friend Don Denoncourt refers to them as smart parameters, which is a great way of thinking of them. (Don’s article “Application Modernization Nirvana,” also in this issue, shows how you can use JavaBeans in a true object-oriented design.) Servlets are Java applications that run on the host. A request to a URL can invoke a servlet, which can then process the request (including any form data entered by the user). When they were first introduced, servlets replaced the more cumbersome Common Gateway Interface (CGI) programs and directly generated HTML code to be sent back to the user. With the advent of JSP, however, servlets can simply instantiate JavaBeans with the appropriate data and then pass them to a JavaServer Page, which will display the static HTML along with the data from the JavaBeans. This way, the HTML designer doesn’t have to know code, and the programmer doesn’t have to know HTML. The JSP acts very much like a display file: The HTML is the DDS, and the JavaBeans are the fields received from the application program.

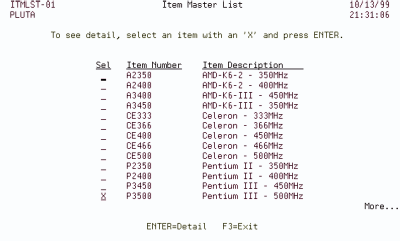

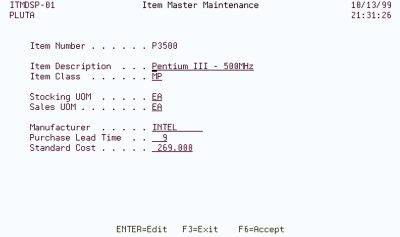

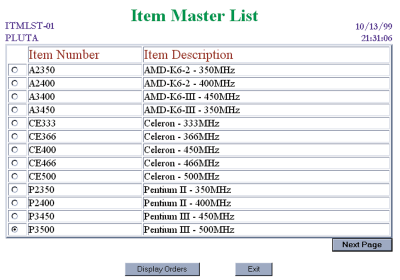

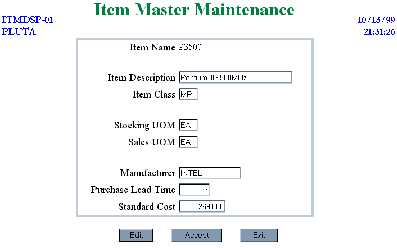

Using this method for a server/client interface, the JSP and servlets can follow a standard format to the point where much of the logic could be programmatically generated as well. The same process that generates the display programs for the green-screen UI client could conceivably create, at least, the servlet and skeleton JSP. The HTML designer can then tweak the JSP as needed for aesthetics. Figures 1 and 2 show typical green-screen panels, while Figure 3 and Figure 4 show their HTML equivalents.

Thick “Client” UI

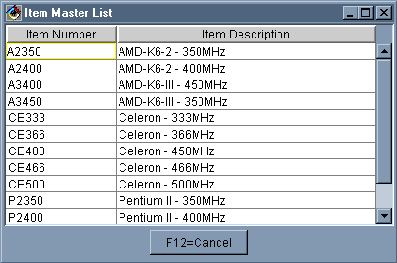

The architecture commonly referred to as thick client requires a fairly substantial application to be present on the workstation. Although we have seen that the workstation portion is actually a UI server, the phrase thick client is still the one most readily recognized in the industry. Primary benefits of the thick client are a more sophisticated GUI and a much greater ability to integrate with other desktop applications. Figure 5 shows the graphical version of the standard list panel. As you can see, the table component (a Swing JTable) makes the interface much more intuitive, at least for users familiar with the desktop metaphor. The user can scroll through the entries in the table by using the scroll bar rather than having to scroll a page at a time by pressing a button. Selecting an item is done with an economical double-click rather than the two-step process of selecting a line and pressing a button. Also, while the user can cut and paste information displayed in a browser window, a thick client allows more sophisticated features, such as drag-and-drop. For example, the user could simply click on the manufacturer information, then drag the cursor over to an email icon, which could automatically launch an email editor with the manufacturer’s email address filled in.

It may actually be easier to programmatically generate thick client UI servers than to generate browser-based servers. This is because the HTML interface is already defined and, so, has limitations. The thick client interface, however, is completely under program control. Written in Java, the classes that make up the interface can be as flexible as you need. You can, in fact, with careful design, create UI server classes that closely mimic the behavior of the green-screen yet still provide the added desktop integration features. For example, my Java Blockmode User Interface (JBUI) classes are a step in that direction

because they provide simple DDS-like construction of complex panels, including list panels.

What About Client/Server?

This article shows that server/client can be used effectively to encapsulate the majority of your existing legacy code yet still provide a number of UI options. However, it is, at best, a partial solution. While server/client may be a good enough answer for the short term, client/server is the more “correct” technology from a strategic perspective. If your eventual goal is to completely reengineer your legacy systems into objects, you’ll probably use client/server architecture as an interim step. The good news is that server/client is an excellent foundation for client/server.

By defining a contract between the UI and the business/application logic, the server/client architecture defines two regions of change, which can evolve independently. For example, you may first choose to redevelop your item master maintenance program into objects. Let’s say you originally decided to use both the JSP/servlet UI technique and a thick client in your server/client approach. (Remember that server/client supports multiple interface techniques simultaneously.) At this point, you have three “pieces” of code: the JSP/servlet user interface piece, the thick-client user inteface piece, and the original monolithic program, which has been modified as an application client.

Now, say you decide to redeploy your JSP/servlet interface as a client/server architecture. The JSP portion doesn’t need to change while you redeploy your legacy code. Instead, you move the application logic from the application client into the servlet, and you use the business logic to develop a true item server program. The servlet still decides which JSP to display and what data to send to the JSP, but rather than a batch program telling the servlet what to do, the servlet uses the legacy application logic to make requests to the item server. The item server supports basic CRUD (Create, Read, Update, and Delete) functions. This way, you can salvage as much legacy business logic as possible for the item server while the legacy application logic moves into the servlet, providing a traditional three-tier architecture.

Having created a true item server to support your rearchitected servlet, you can then rewrite your item maintenance thick client as a true client. (Remember, in the server/client architecture, the code running on the workstation is actually a user interface server, not a true client.) It will make direct requests to the item server, retrieving, adding, and updating records as needed. Your thick client can still provide all the drag-and-drop facilities; in fact, it can provide better features because it has servers to access. Rather than simply rely on the information passed in the “display buffer” of the server/client design, the client in a true client/server architecture can actually fetch additional information as needed, provided a server is written to support the additional requests. As more of your applications are redeployed into servers, your clients can become more sophisticated.

Revitalize

I hope I’ve been able to show you the benefits of revitalization as a first phase of legacy redeployment. Revitalization provides a powerful graphical interface without the need for costly redesign and rewrite. Indeed, for many applications, particularly those run rarely or by only a few people or those with a limited life span, revitalization may be the only phase required. However, unlike screen-scrapers or CGI, revitalization is not a technological dead end. In particular, the JSP/servlet approach provides a solid foundation for moving on to true object design as needed, with minimal disruption to your users. So whether you just want to get your existing application on the Web or entirely redeploy all your code into objects, revitalization via server/client design is the first step on the journey.

Figure 1: This is a typical green-screen list panel.

Figure 2: And this is a typical green-screen maintenance panel.

Figure 3: Here is the list panel redeployed in HTML.

Figure 4: This shows how a maintenance panel would look in HTML.

Figure 5: This is a Swing-based thick-client list panel. The window is sizable and movable, as are the individual columns in the JTable.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online