Ch-ch-ch-ch-Changes

(Turn and face the strain)

Ch-ch-Changes

Just gonna have to be a different man

Time may change me

But I can't trace time

—David Bowie, Changes

Note that when I say "simple," I preface it with "relatively." That's because even in the days of a single language and a single platform, we still had plenty of issues to go around. First, it really wasn't a single language: We typically had DDS, RPG, and CL. But even though some of us had COBOL and a few of us even had C, in general only a few languages made up any one application.

And yet we still had problems getting things out the door. At SSA, we had an entire team of people who were in charge of wrapping and releasing each new version of the software. Self-dubbed the "weekend rats" because the job typically occurred over the 64 hours between Friday afternoon and Monday morning, this team had an entire script of things to do to ensure that a release was completely and correctly built. The script was carefully honed over years of practice with releasing software, chock full of the knowledge of dozens of releases that literally spanned decades—and yet I don't think I remember a single release going out that didn't have some object missing or some program at the wrong version. Whether it was a level check on a rarely used logical or a missing message in a message file, something inevitably went wrong.

And that was with three languages.

The New Challenge

Fast forward to today. A typical application can easily require a half-dozen or more languages, especially if you consider things like HTML and CSS. Not only that, but these files may need to be distributed to different platforms and possibly even multiple machines in each platform. And although the transfer might be as simple as performing a SAVRST of a message file from one partition to another, it could also be as complicated as sending EAR files via FTP to multiple PCs and then executing commands on the PCs to install the EARs.

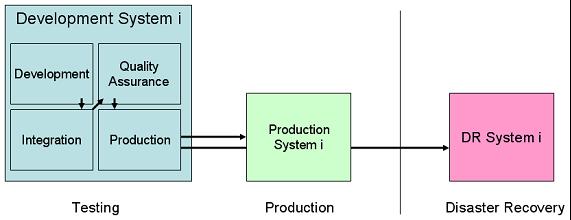

Figure 1: This is a relatively simple application deployment environment. (Click images to enlarge.)

Take a relatively simple scenario. Figure 1 shows a company with two iSeries boxes (this could be virtual, using two partitions on the same machine, but that doesn't really change the scenario). The development machine has several environments, from individual developer areas on through integration, QA, and production. The production machine has only one, which is intended to be a mirror of the production environment on the development machine. In addition, the company has an offsite disaster recovery machine.

So, you need to promote objects (the dark, unbroken arrows) from development to integration, to QA, and finally to production. This is relatively simple and typically involves just a CRTDUPOBJ. Once the objects are in production on the development box, they then need to be transferred over to the production machine. This will definitely require some sort of SAVRST. And finally, anything that is sent to the production box should also be sent to the disaster recovery machine. The exact mechanics for this process depend greatly on how you have your disaster recovery procedures defined.

Multi-Tiered Architectures

Even after this, all you have is a way to support a simple green-screen application. And this is as far as IBM's tooling (Application Development Manager, or ADM) ever got. Other vendors have significantly surpassed that original design, which is why IBM decided to drop the support for ADM with V5R3 of i5/OS.

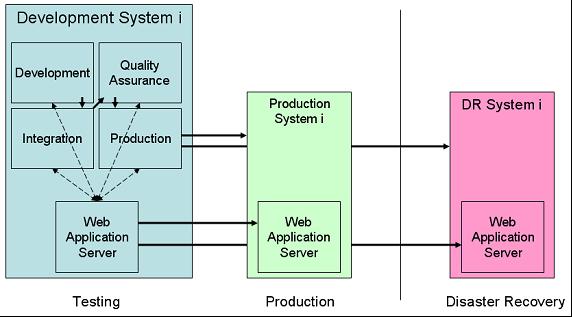

Figure 2: Next, add Web requirements into the mix.

Figure 2 shows your basic Web application development environment. In this particular scenario, I'm going to assume that the Web application server runs on the System i. Let's further say that the application is a very simple architecture, one in which JSPs talk to RPG service programs to retrieve and update data. I'm using dotted lines to show the call relationships. You should note that, in the development phase, the Web application server may need to talk to multiple environments on the development machine. This depends greatly on whether your Web components are hand-crafted or generated and how you set up your Web application server. If you need different instances of your Web application for each environment, you're going to have to move the Web components from one environment to another. With a tool that generates the components, you'll need to re-run the generation step at each promotion.

The only simpler scenario is an RPG CGI environment in which there is no Web application server and all the Web programs are also written in RPG; such a system could theoretically be as simple as the one in Figure 1. In reality, though, it just wouldn't be that easy. All but the most basic of applications require some Web components such as server-side includes, JavaScript files, and style sheets that would have to be synchronized between the various boxes.

So realistically, once you go to the Web, you now have another set of objects that need to get from one machine to another. Typically, these can be transferred via FTP. IFS-based SAV and RST commands also exist; these function equivalently to the SAVOBJ and RSTOBJ commands, except that they're in the IFS system rather than the traditional QSYS environment. Additionally, if your deployment environment does not support hot deploy, you will have to create and move application-level objects such as Web archive (WAR) or enterprise archive (EAR) files and then run a deployment script on the target server.

Multi-Platform Deployments

Then you get to the next configuration. In this scenario, the Web application server resides on a box separate from the primary business logic. Several reasons exist for moving the Web application server off the System i. For example, putting the Web application server in the demilitarized zone (DMZ) ensures that the machine holding your mission-critical data and processes is not vulnerable to even the most basic of attacks, such as a denial-of-service (DOS) attack in which large numbers of packets are directed at your IP address and can conceivably slow down the non-TCP/IP functions in your server.

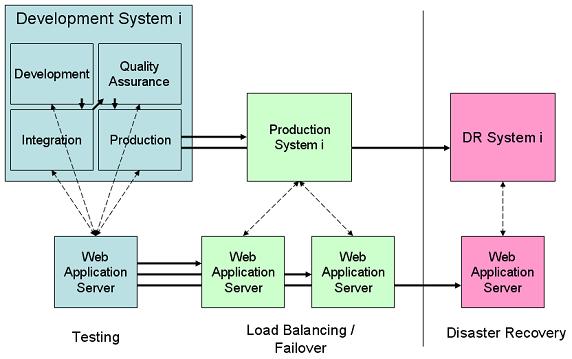

Figure 3: Moving the Web application server off the System i has benefits at a cost in complexity.

Workload also factors in. The memory use of the traditional RPG-based workload of the System i is incompatible with the memory requirements of the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Extensive empirical data shows that sharing memory between RPG and Java reduces the effectiveness of both. So any Java application on the System i (such as a Web application server) should have its own dedicated memory pool. An easy way to do this is to run the Web application server in a second partition or even on another, small System i machine.

Another possible route is to go to another platform entirely for your Web server. Memory on the System i is quite expensive compared to other platforms, so it can be cost-effective to move the Web application server to a separate, dedicated machine, either Windows- or UNIX/Linux-based. With a properly designed application architecture, you may even find that a dedicated PC-based server is more responsive than the same application on the System i, provided that the communication link between the machines is adequate. I've yet to find an application in which a gigabit Ethernet line was not adequate, but my feeling is that if there is a weakness in the architecture, this is the place you'll find it.

Of course, the other weakness is that the components need to be moved. Each machine layer increases the complexity of the object distribution process. Note that in Figure 3 I snuck in something: an extra Web application server for load balancing and failover. While I'm not trying to stir up any rancor, the truth is that unless you spend a whole lot of money for a server-class machine (with things like dual NICs and RAID disk and so on), then a Windows or UNIX machine is less reliable than a System i. That being the case, you probably want to have at least one failover machine. The good news is that once again a properly designed architecture can take advantage of this extra hardware, and you can conceivably also use any failover machines as additional load-balancing support during normal operations.

Thick Clients

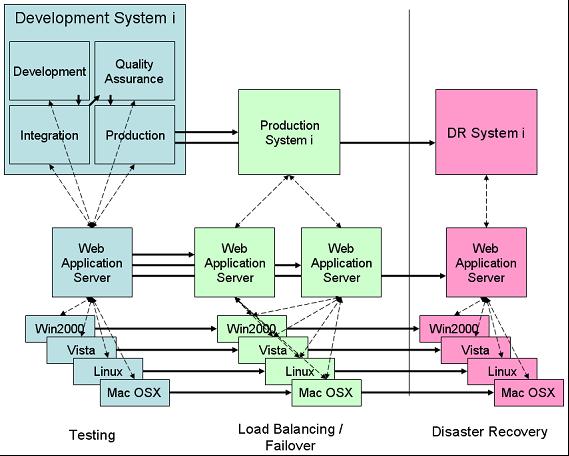

This very issue is the one that I think completely kills the idea of thick-client development, at least for any sort of public access. Take a look at Figure 4.

Figure 4: The complexity of thick-client support can easily become overwhelming.

You'll see that just supporting the primary operating systems—the two flavors of Windows, Linux, and Mac—adds a level of complexity that could be mind-numbing. Even if you have the ability to somehow safely download your thick-client software to a user whenever a change is made, just imagine the number of environments you would need in order to be able to adequately support a true change management system throughout the various phases of development.

You could certainly remove some of the target client platforms in your disaster recovery configuration, but that's only a small portion of the overall complexity. And while it might be argued that the Web application server tier is unnecessary in a thick client, I think that any modern architecture would involve rich clients communicating via Web services or a service component architecture (SCA) protocol to a Web application server. The fundamental idea of service-oriented architecture (SOA) is to remove the tight binding that might otherwise exist between a client and server.

If you are deploying an Intranet application, or in some cases even an Extranet, in which you have control over the client platform, you can probably reduce the complexity correspondingly. But in my opinion, the complexity of a thick-client environment precludes its use in all but the simplest configurations.

Multi-Tenanted Systems and Other Complications

I talked in a recent article about multi-tenanted systems as one of the logical outgrowths of the Software as a Service (SaaS) movement. One of the biggest issues with multi-tenanted systems is that, by definition, you're going to have to support multiple development branches. Different clients will have different needs, and it's unreasonable to try to support all changes with switches in the code. This is actually the reason that semi-custom code is so incredibly powerful. I mentioned it in one of the forum discussions: You can program 80% of the code the same for everyone and then code the 20% that makes each client's business unique to the exact specifications required.

However, to do that you need a lot of environments. Picture Figure 3 but with additional environments for each of a half-dozen clients, including all of the test environments required. You probably don't have enough pixels on your screen for me to draw a readable diagram. However, if there's a machine that's built to handle this sort of environment, it's the System i. By using library lists, you can easily set up literally dozens of environments. The trick is to tie in the Web component side of the equation so that programmers can easily and flawlessly promote objects to the appropriate locations within the deployment network. This includes both mirrored local servers and remote disaster recovery machines.

It can be done, but I don't think it's being done today. I haven't seen a single product in which, for example, a JSP and an RPG program are tied together for promotion (in the same way that some System i products tie together RPG programs and their associated display files). Nor have I seen a product in which you can associate an object on the System i with one on a Windows box and then make sure they get promoted properly (especially when the Windows object needs to be promoted to multiple mirrored servers).

Hello, Joe? Got a Point Here, Buddy?

OK, if you've read this far, you're probably wondering why I bring all of this up and especially what in the world it has to do with WebSphere and WDSC in particular. Well, I recently had an email conversation that included discussion of the sunsetting of IBM's ADM product and whether WDSC had a replacement.

The current (but not particularly welcome) answer is that there are lots of replacements, but they're all commercial products. Each has a slightly different take on the issue, and I'd love to see MC Press do some sort of comparison of the products, but for the purposes of today's article, it's enough to know that all solutions are for-fee third-party solutions, and none of them are particularly inexpensive.

Eclipse, the underlying foundation of the WDSC product, contains embedded support for CVS, the "industry standard" source management system, but there's really no corresponding support for building components much less deploying them, and CVS isn't particularly System i–savvy. The Rational product line—of which WDSC is ostensibly a member—comes with a built-in solution called ClearCase, which is somewhat more System i–aware, but it's definitely not tightly coupled with i5/OS. You can read more about how that particular tooling works here.

No, the unfortunate truth is that right now there is no real multi-platform, multi-lingual, multi-tiered System i–aware version control, source management, build-and-deployment tool available for free. And there may not be one for a fee, either. I've had minor dealings with some of the packaged solutions and have extensive experience with custom-developed deployment systems, and I'm not sure that any of the change management vendors have everything needed for all of the scenarios I've provided here. On the other hand, I'm certainly no expert at these tools, and I'd love for the vendors to add their own comments. And my guess is that some of you would enjoy a product comparison or at least some reviews as well.

I do know this, though: The next release of Rational is already out, and the next release of WDSC will be hot on its heels. At the same time, there are some interesting things brewing over at IBM that we should hear about in the next week or two that could significantly impact System i developers and particularly those of us who rely on WDSC as our primary development tool. So stay tuned, and we'll get you all the late-breaking information as it becomes available.

Joe Pluta is the founder and chief architect of Pluta Brothers Design, Inc. and has been extending the IBM midrange since the days of the IBM System/3. Joe uses WebSphere extensively, especially as the base for PSC/400, the only product that can move your legacy systems to the Web using simple green-screen commands. He has written several books, including E-Deployment: The Fastest Path to the Web, Eclipse: Step by Step, and WDSC: Step by Step. Joe performs onsite mentoring and speaks at user groups around the country. You can reach him at

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online