You see, you can't please everyone, so you got to please yourself."

--Ricky Nelson

Last month's quote was philosophy; this month, it's rock 'n roll. At least I'm eclectic, eh?

In columns to date, I've pretty much focused on getting data into WebSphere. I've covered everything from installation, to configuration and setup, to database access. I thought I'd take this opportunity to focus on the other side of the coin: getting data to the user. The user interface (UI) is a relatively large subject, including things like application architecture (pure servlets, JSP, or JSP Model II?) and application organization (do I use server-side includes or the include method?). But to get started, I'd like to spend this column on a single, specific issue: which browser (or browsers) to support.

This column is not about which browser is better to use to surf the Web; that's a personal decision, and it depends as much upon your own preferences as anything else. This column is also not meant to start an argument about which browser has better HTML support or which has better market share--although those questions may play a part in your decision-making process, so I'll present my findings on those matters. Instead, this column is about deciding which of those factors is important to your application, determining from there which browser or browsers you need to support, and finally, implementing that support.

Without going into too much detail, I'll introduce the various browsers.

- I'll identify the primary differences between these browsers.

- I'll outline the various support options.

- I'll present the factors to consider when making your support decision.

Who Are the Players?

There are more browsers out there than you might think. While we usually only hear about Internet Explorer and Netscape (which combined account for over 95% of the users, regardless of who is doing the accounting), a host of others exist. For instance, a whole set of browsers are based on the Mozilla project, as well as a number of special-purpose or independent browsers.

The Big Two--Internet Explorer and Mozilla/Netscape

In order to talk about browsers, you have to first consider the big two: Internet Explorer and Netscape. Netscape used to be the leader in the industry--in 1996, Netscape owned 87% of the market share. Since that time, Internet Explorer has used the dominance of the Windows desktop to completely alter the browser marketplace. Now, Internet Explorer has 90% or more of the browser audience, depending on where you get your statistics. If you're unfamiliar with Internet Explorer, then you're probably running a Linux or Macintosh environment, and that will definitely sway your decision-making process, as you'll see a little later in this column.

On the other hand, if you're a Microsoft shop, you're probably exclusively using Internet Explorer, and you may not be familiar with Netscape or Mozilla. In fact, the two are very closely related. In about 1998, Netscape released the code for Netscape Communicator to the public, and thus began the Mozilla open-source project. Since then, Mozilla and Netscape have shared an uneasy dual development path. Netscape continues to release commercial products based on the Mozilla code base, while the Mozilla project seems to be trying to branch off and gain its own unique identity, including the release of its own version of the browser, called simply Mozilla. Much of the friction between these two paths stems from product licensing issues. While it would take an entire column to even skim the surface of the debate, the primary issue is that Netscape wants all the code to be licensed under the Netscape Public License (NPL), which is different from the standard open-source license, the GNU General Public License (GPL). Netscape insists the NPL was designed to make open-source "more commercially viable," but whatever the intent, the NPL has been less than palatable to open-source developers. Because of this, the Mozilla project developed its own licensing strategy, the Mozilla Public License (MPL). At the same time, the open-source community developed another license, the GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL). These various licensing schemes have differing degrees of compatibility, and the squabbling here underscores the tension that can occur when the open-source world and the commercial software world collide. At this time, the Mozilla project is attempting to address incompatibilities by relicensing the entire project under an MPL/GPL/LGPL tri-license (their words, not mine). Once that happens, it is uncertain what will become of the relationship between Netscape and Mozilla, but at this writing, the recently released Netscape 7.0 seems to be still based on the Mozilla project code.

Despite this uncertainty, Mozilla seems to be, if not exactly flourishing, at least holding its own. A number of applications based on the Mozilla source code are available, including not only a handful of browsers, but also some non-browser applications, as the Mozilla project continues to extend beyond the original browser code.

Other Browsers

There are some other browsers out there, too. The most popular seems to be Opera, a small, fast proprietary browser that's available for multiple platforms. Linux also has a variety of Mozilla-based browsers as well as a number of independent browsers, such as Konquerer. Interestingly enough, some users insist on clinging to non-graphical browsers, such as Lynx and w3m, which brings up some very interesting support issues.

What's the Difference?

There are really only two areas where most browsers differ in ways that will affect a Web application: HTML and JavaScript. While all but the most off-the-wall browsers are reasonably compatible for basic HTML, you'll start to see the differences once you begin to implement techniques such as Cascading Style Sheets (CSS). And the JavaScript problems arise not so much from basic JavaScript support, which again is relatively compatible across the board, but instead from the more advanced capabilities that require the Document Object Model (DOM).

HTML

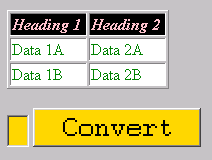

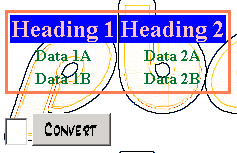

The basic HTML syntax is pretty stable, and therefore so is basic HTML support. In areas where the language is being extended and is still in its formative stages, such as XML and XUL, these browsers are wildly incompatible. If your target audience cannot be narrowed to a specific browser, you might want to steer clear of these for the time being. However, there is one area in particular that, although still evolving, is crucial to good Web application design, and that is CSS. Think of CSS as sort of the DDS for HTML. The exact same HTML codes can be sent to a browser, but depending on the style sheet in place, the page can be rendered entirely differently. For example, the two images in Figure 1 were generated by exactly the same HTML code, but with different style sheets.

Figure 1: These images were created with the same HTML code but different style sheets.

Not so long ago, CSS support varied widely among the browsers. Now, most browsers have pretty consistent support for the first version of CSS, known unsurprisingly as CSS1. The newer version, CSS2, includes features that allow basic HTML to have some really dramatic effects, but today only Netscape/Mozilla seems to support the most advanced features.

JavaScript

Whereas CSS2 support is probably more important for applications that need that "Webby" look, JavaScript support is more important for applications that need to provide the functionality users associate today with the 5250 interface. Support for features like function keys, keystroke editing (for uppercase-only or numeric fields), and other advanced features of character-based interfaces are only available by using JavaScript--and more specifically, JavaScript support for the DOM.

The DOM allows you to treat an HTML document as a collection of objects. That is, you can enumerate, inspect, and modify all the individual pieces that make up the document. Forms and fields, paragraphs and tags--all can be modified using this approach, allowing you to dynamically change the contents of a page programmatically. Not only that, but the DOM also allows you to define "event handlers," which allow you to intercept, interrogate, and even change user events, such as keystrokes and mouse clicks.

Combined, these capabilities allow you to create a user interface that is as interactive and powerful as the 5250 interface we're so accustomed to. I've designed simple JavaScript functions that allow me to create uppercase-only fields, for example, or to simulate the auto-record-advance feature of DDS.

The problem is that the DOM is implemented differently--very differently--by the two major browsers. Internet Explorer has a very flexible and powerful implementation that is unfortunately entirely incompatible with the model Mozilla uses. Not only that, the Mozilla implementation is less complete, in my view, because it is difficult or impossible to change an event's behavior. While you can at least ignore some events, it's harder to convert one event to another, such as converting a lowercase keystroke to an uppercase keystroke.

Including CSS or JavaScript

An important consideration for either CSS or JavaScript programming is the technique you use to include the code in your HTML. Either type of code can be embedded directly into the HTML using tags ( for CSS, for JavaScript). When programmers start out using either technology, they often use this technique to quickly see how changes affect their code. However, both CSS and JavaScript support the ability to include external files. For CSS, the files typically have a .css extension, while .js files are usually used to contain JavaScript code. Using an external file requires a slightly different tag syntax. External CSS files are included using the tag, while external JavaScript files still use the

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online