Some unsettling news recently added anxiety to the daily avalanche of already unsettling news. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced its approval of the use of a minute device that can be embedded under the skin of patients in hospitals. This device allows hospitals to instantly know all essential details about the person's medical data, including blood type, allergies, etc. Think about it: a tiny chip under your skin that tells someone all about you. No wonder this news got so much attention. And for many people, it was the first time they had closely looked at Radio Frequency Identification (RFID), a revolutionary and justifiably worrisome technology that is already being used more widely than most people realize.

Briefly, RFID is an integrated circuit (IC) chip the size of a pinhead that can be programmed with many bits of data and attached to a mini antenna. This device is activated by an electromagnetic field that initiates a process of transmitting the chip's data to a nearby receiving antenna and relaying it to a back-end computer. As you can imagine, the applications are endless: from medicine to manufacturing, from security to logistics, from transportation to just about anything you can think of. Of course, it's also easy to imagine more nefarious uses, like stealing identities and invading privacy, which are very real concerns. Still, the benefits are remarkable in terms of positive identification, efficiency of processes, improvement of quality, and reduction of theft and forgery.

The world's largest retailers are heralding RFID as a technology that will save them billions of dollars over the next several years. Perhaps you already know that Wal-Mart's 100 largest suppliers were mandated some time ago to begin identifying their pallets and cases with RFID tags by January 1, 2005. Although it looks like this date is going to slip yet again as the standards and technologies are still being sorted out, most manufacturers and distributors aren't being lulled into complacency about RFID. They know (or should) that compliance will be inevitable. Yes, a few kinks must still be worked out, but with the dropping cost of implementing RFID, it won't be long before it becomes the standard for product identification.

Wal-Mart is not the only large entity that has recently put its largest suppliers on notice that RFID will soon be a requirement. Most notably, Albertson's, Target, and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) have warned vendors that RFID will be required in the next year or so. The initial benefit of the technology is that it eliminates the line-of-sight and serial scanning limitations of barcodes; for instance, a pallet of merchandise can be instantly inventoried without taking the pallet apart and scanning each case. Plus, there are many other potential savings once the technology is perfected; for example, instant warehouse inventories, automatic triggering of restocks/reorders when products leave store shelves, instant tracking of recalled products, and much more.

Theoretically, RFID is not much more complex than barcodes. Like barcodes, each tag contains an identifying code that is associated to other information in back-end databases. In application, however, RFID can be complex because of the many issues regarding standards, environmental factors, and an often-challenging implementation process. Despite this, RFID has already reached astonishing levels of versatility, economy, and pervasiveness, making it a rapidly growing means of identifying and tracking merchandise, assets, individuals, vehicles, and more.

A Little History

During World War II, the Allies unceremoniously introduced RFID as a way to identify which aircraft entering England via the English Channel were "the good guys." A radio frequency transponder attached to Allied aircraft broadcast an appropriate response to an "interrogating" radio signal sent from installations on the coast of England, thus alerting defense crews on the ground that the aircraft was friendly. In the 1970s, this same concept of electronic interrogation/response was shrunk down to fit on IC chips with small, attached antennas for use in animal identification, factory automation, and military applications. Through the 1980s and 1990s, as RFID technology became more cost-effective, other common uses naturally arose, particularly around transportation management and personnel access. The fact is, you may have been carrying around an RFID tag on your company ID tag or your toll-way tag for years without ever knowing it.

Today, RFID is used widely in the security and transportation industries. It comes as no surprise that the security industry was an early adopter of RFID and continues to be a very large consumer of the technology. RFID chips are commonly embedded in identification badges and in rigid barcode labels to track the whereabouts of equipment. In the transportation industry, prepaid toll road tags and parking passes often use RFID to identify you and verify your account status. RFID has been used for years to identify semi-trucks, trailers, and shipping containers as they pass in and out of freight yards.

Now, RFID is being adopted in supply chain applications to automatically track inventory as it is shipped, received, and moved around a warehouse, and it's being used in manufacturing processes to ensure the proper identification and routing of components and sub-assemblies in manufacturing workflows. Additionally, RFID is used to track high-value products for service and warranty purposes. Many new cars and even tires have embedded RFID tags for this very purpose.

Anatomy of an RFID Tag

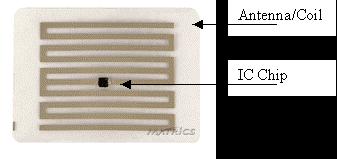

An RFID tag (also called a "transponder") is made up of an IC memory chip and an antenna, and in some cases, a battery to boost the signal. RFID tags are available in a spectrum of shapes and sizes: They can be thick and rigid or thin and flexible enough to be embedded within an adhesive label and run through a label printer. Tags can be screw-shaped to identify trees or wooden items, while credit-card shaped tags are commonly used in security access applications. Long, paper-thin, disposable tags are used to identify pallet loads and caseloads of merchandise to entities in a supply chain. And, as mentioned, very small tags can be inserted under the skin for human and animal ID purposes. The type of tag simply depends upon what it needs to deliver in terms of quantity of information, range of transmission, and the operating environment.

Following is a diagram of a simple RFID tag. As you can see, there isn't much to it in its basic form. In fact, with read-only tags, the chip may be only a little larger than a pinhead; the rest of the size is taken up by the antenna, the size of which is dictated by the needed detection range.

A simple RFID tag (courtesy Matrics)

Typically, the larger the tag, the larger the memory capacity, the greater the durability, and the more extended the range in which the tag can be detected. In addition, different tags transmit at different frequencies, depending on the industry where they are used and the reception/transmission range needed. RFID allows hundreds of tags to be read simultaneously, and individual tags can be read at remarkable speeds, often as fast as 100 milliseconds per tag.

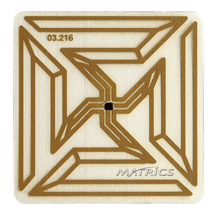

Square chip/antenna inlay for carton tags (courtesy Matrics)

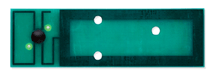

Round chip/antenna inlay for CD/DVD tag (courtesy Texas Instruments)

Interior/exterior of rigid semi-trailer tag (courtesy Intermec)

Interior/Exterior of small cylindrical tag (courtesy Texas Instruments)

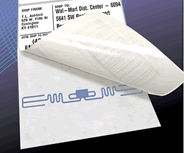

Barcode label with embedded RFID tag (courtesy T.L. Ashford)

Livestock ear tags (courtesy Destron)

Tags can be read-only (programmed once only), read/write-capable (reprogrammed multiple times), or a hybrid of the two (certain data can be permanently written--for instance, a serial number--while other data can be changed or added as needed--for instance, purchase and warranty information). Read-only tags are preprogrammed or encoded when they are manufactured (i.e., when large quantities of tags have the same information) or are programmed just prior to the tag being attaching to an item, sometimes by the same device that detects and reads the tags (the reader).

RFID tags are either "passive" or "active." Passive tags are activated by the energy field that is transmitted by the reader. Because passive tags do not have their own power supply for transmitting encoded information to the reader, the distance they can be located from a reader is greatly limited. Active tags are each powered by their own battery, which adds cost but significantly extends the detection range. The battery power of active tags enhances read/write capabilities (data on tags can be revised or erased thousands of times), allowing greater versatility of use. Of course, active tags are usually more expensive and heavier than passive tags; therefore they're typically not used in supply-chain applications. Active tags can cost several dollars each to produce, while passive tags can be purchased for as little as 25 cents each (but only at quantities in the millions). Because of the price, only passive tags are used in the supply chain, and then mostly on high-ticket items or at the case and pallet level; however, within the next few years, it is expected that the price of passive tags will drop to a few cents each, at which point it is likely that RFID will begin to replace barcodes on individual products.

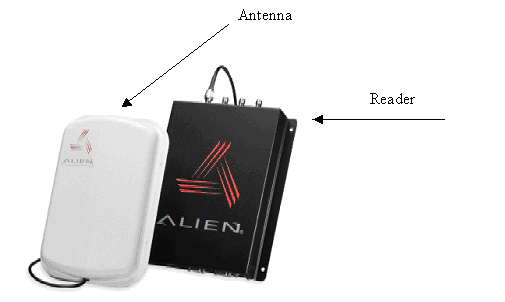

RFID Readers/Interrogators

Another critical component of RFID technology is the "reader" or "interrogator," which transmits an energy field that causes a tag to activate and then transmit the data stored within its chip. If the tag doesn't have a battery, the reader's energy field provides the necessary power for the tag to transmit its information back to the reader, although the detection/transmission distance is significantly reduced. When this data is received by the reader, it's passed along to back-end computing systems in order to initiate transactions.

Readers can be fixed or portable, like barcode scanners. Fixed readers range in size from floor models that are as tall as a person to smaller handheld units the size of handheld barcode readers. It simply depends on the application. These units typically collect data on products traveling through "choke points" such as dock doors, conveyor belts, gates, and doorways. Portable, wireless readers can be attached to forklifts and collection carts.

Not only do readers locate, activate, and receive transmissions from RFID tags, many of them have the capability of sending data back to read/write-capable tags to either add or replace information.

RFID reader and antenna (courtesy Alien Technologies)

Handheld reader/interrogator (courtesy Intermec)

RFID in Supply Chain Applications

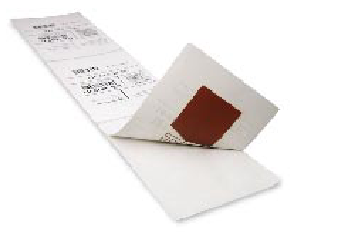

To comply with the mandates of large retailers to have RFID tags that identify merchandise on cases and pallets, a special RFID tag called a "smart label" is often used. A smart label is essentially a barcode label that has a flat RFID tag embedded inside.

Flexible "smart label" (courtesy T.L. Ashford)

The RFID tag within smart labels is typically coded with an Electronic Product Code (EPC) and any additional information required by the customer. The cost for smart labels is currently about 40 to 50 cents each, while the printer that accommodates both the printing and programming of smart labels costs between $1,500 and $3,000. In addition, it is necessary to ensure that back-end software can accommodate the RFID data passed to the printer/encoder. For some companies, this latter task can be expensive, especially if the software needs to be changed to accommodate RFID data.

EPC Codes and Standards

The EPC (a.k.a. Global Trade Item Number, or GTIN) is the basis of an enhanced global supply chain network that RFID is propelling. The EPC is substituted at the pallet and case level for the well-known Universal Product Code (UPC). There are two reasons that EPC codes are necessary when RFID is used in supply chain applications: First is to create globally accepted standards for product identification. Products around the world must be identified and described in a standardized way, and communications about product attributes between partners must also be standardized (UPC codes are limited to use only in certain geographies). Second, EPC provides the capability to uniquely identify every item that is produced. For instance, each gallon of milk can potentially have a unique ID number that indicates the manufacture date, the plant where it was bottled, the lot number, the expiration date, etc.

Today, serial numbering is not yet cost-effective unless the item has a high value, but once tags cost a few cents each, serial numbered RFID tags will likely appear on all items. This will provide many benefits to retailers; for instance, a retailer will be able to automatically detect when shelves need to be restocked (which can in turn trigger the automatic generation of purchase orders) and will be able to quickly locate and remove from sale products that are defective, out of date, etc.

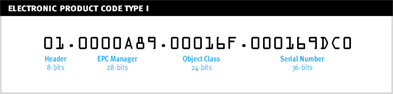

EPC codes are typically 96 bits in size (24 four-bit characters) and are programmed onto RFID tags to identify the manufacturer and type of product (as barcodes do today). In many instances, companies use their present UPC code within their new EPC code. Until the cost of RFID tags reach cents-per-piece levels, many companies will use RFID codes only to track items at the SKU level (identifies manufacturer and product type) and then only in case and pallet units of measure. Even so, this complies with the mandates of Wal-Mart and the like.

A 96-bit EPC code (courtesy Lansa)

In the above example, the portion of the code shown as the "EPC Manager" identifies the company, while the portion of the code shown as the "Object Class" identifies the brand, model, size, unit of measure, etc. Finally, the last portion, the "Serial Number," can be used to optionally identify the individual product.

Before a company can program EPC codes into RFID tags to meet basic RFID compliance requirements with major retail customers, they must ensure they have EPC codes that meet global standards, and the EPC codes must be must be registered on the Global Data Synchronization Network (GDSN). Essentially, GDSN is a private "Internet" for global trading partners that allows partners to access standardized information about a product. To register EPC codes, a company must subscribe to a trading partner that is a member of the GDSN. Trading partners include UCCnet, Transora, WorldWide Retail Exchange, and many others.

Once a company has standardized and registered EPC codes, these need to be associated with inventory items in the back-end systems. Third-party software is required to take the EPC code data and write it to the RFID tag, usually a "smart tag" that is encoded as it passes through a special label printer/encoder. The printed/encoded tags are then applied to cases and pallets.

The Potential of EPC

The purpose of EPC codes is to create globally accepted standards for product identification. Products registered on GDSN can have up to 200 standardized product attributes that can be seen and shared by all trading partners (and potential trading partners). GDSN is currently in its formative stages, but eventually the benefits of being part of the GDSN will be significant. For instance, when a vendor introduces a new product and its EPC code is registered on the network, a "catalog item notification" can be automatically distributed to all retailers connected to the GDSN. These retailers can instantly access complete standardized product information and decide whether to stock the item. If a retailer decides to purchase, an instant notification can be sent to the vendor. In addition, if a vendor makes any change to the product attributes, a "catalog notification" can be automatically distributed to all retailers advising of the change. Again, this system can also be very valuable for recalls because vendors can immediately know all of the purchasers in the supply chain.

EPCglobal Frequency Specifications for RFID

An organization called EPCglobal has created different specifications for the frequency, encoding characteristics, and other attributes of RFID tags and has become the standard in supply chain applications. EPCglobal is an affiliate of the United States' Uniform Code Council (UCC) and Europe's EAN International (EAN). Both of these organizations maintain the EAN.UCC System, which for years has managed worldwide barcode numbering assignments and barcode symbology standards.

Unfortunately, there is still not a single agreed-upon standard for RFID tags that are used in supply chains, although it is likely that one will emerge soon. For now, different retailers have decided to go with different "classes" as defined in EPCglobal specs:

Version 1.0 (Generation 1, or Gen1)

- Class 0 tags: These tags are read-only (programmed only once), have 64- or 96-bit memory capacities, and operate in the UHF frequency band between 868 and 930 MHz.

- Class 0+ tags: These tags are identical to Class 0 tags but are rewriteable.

- Class 1 tags: These one-time programmable (OTP) tags can be updated once after being encoded with an EPC number; they have a 96-bit memory capacity and operate between 868 and 930 MHz.

Version 2.0 (Generation 2, or Gen2)

Generation 2 (Gen2) tags were recently developed to overcome concerns regarding interference by environmental causes, such as lighting, that arose from Gen1 tags. In fact, Wal-Mart and the DoD now require Gen2 tags when their suppliers ship with RFID tags. It appears that most other larger retailers that intend to require RFID will follow suit. There is currently a single class for Gen2 tags, which has a memory capacity from 96 to 256 bits. The operating frequency band is 860 to 960 MHz, which also happens to be consistent with ISO 18000-6 standards, allowing this standard to better integrate with other global standards.

Brand New Wonder or Brave New World?

Certainly, the genie is out of the bottle when it comes to RFID, and like any other technology that can be used for good or ill, it needs to be closely managed and regulated. It is critical that the public be made aware of how this technology will benefit them and when they need to be cautious. Of course, there are urban myths floating about that the government will soon require tags in everyone's forearms and the IRS will have agents disguised as Maytag repairmen cruising the streets with long-range readers and taking instant inventories of valuables. But regardless of the myths and the very real dangers for abuse, there is no doubt that organizations and individuals are already experiencing tremendous efficiencies and conveniences from the technology. Either way, we have only seen the beginning of how this technology will affect our lives.

Bill Rice is a freelance technology writer and marketing consultant, as well as a regular writer for MC Showcase Online. He can be reached at

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online