Look beyond the smoke and mirrors of marketing jargon.

A lot of companies are evaluating cloud services to extend or replace in-house IT services at a lower cost. The reasons for considering cloud services include access to more affordable and/or more powerful applications, legacy migration concerns that result from outdated operating systems (e.g., Windows XP), IT staff reductions, capacity planning, etc.

But what are the economics behind the move to cloud? Will outsourcing services to the cloud really solve the economic challenges of in-house IT, or will they exacerbate existing IT service issues and end up costing more?

Of course, there is no simple, single answer to these questions because so much depends on the types of applications that are being run and the kind of cloud services a company is considering.

In this article, we'll examine the kinds of cloud services, what they offer, and how their economics might compare to the traditional architecture of the traditional internal IT department. We can't answer every question about the economics, but we'll point to some further reading that can help you and your management dig deeper.

First, let's define the kinds of cloud services that are offered today before we look at how their economics might compare to the same or similar services performed by an in-house IT staff.

Second, we'll need to establish some criteria for decision-making to determine if the cloud service will meet the goals of management. For instance, is the goal to reduce overall costs for the entire IT function? Is it to reduce infrastructure and/or maintenance costs? Or is it simply to gain more capacity or functionality more rapidly?

Finally, let's look at the different application architectures and see how cloud computing might impact the functionality and the overall costs of the implementation.

So let's start with the general definition of cloud, and then move into definitions of services contained in the cloud.

What's in the Cloud?

Cloud has multiple elements that differentiate it from other IT services (such as data-center services, etc.). Cloud should provide the following elements of service at minimum:

- On-demand self-service—The ability for an end user to sign up and receive services without the long delays that have characterized traditional IT

- Broad network access— The ability to access the service via standard platforms (desktop, laptop, mobile, etc.)

- Resource pooling—Resources are pooled across multiple customers

- Rapid elasticity—Capacity can scale to cope with demand peaks

- Measured service—Billing is metered and delivered as a utility service

What cloud is not is simply a computer sitting on the other end of an IP connection serving data. It is not simply a web page or portal, though the services delivered may include web browser services, and the interface most commonly implemented used is a web browser.

Cloud is instead an elastic architectural structure that delivers its services widely across a network, sharing or pooling its resources among multiple customers so it can deliver rapid capacity growth on-demand and can be billed as a measured service.

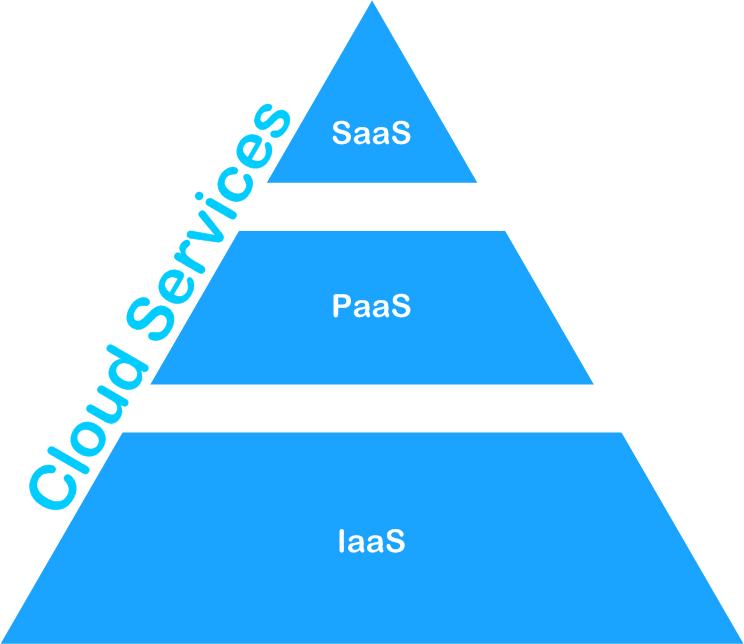

Three specific service structures are currently sold in the cloud marketplace: Software as a Service (SaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS). Each has its own (if overlapping) dimensions within a cloud computing structure.

Software as a Service

SaaS provides web access to commercial software, managed from a central location, delivered in an "application server" model that does not require users to handle software upgrades or patches and provides integration APIs between different pieces of software. An example of SaaS would be email services such as Gmail or Yahoo Mail.

Platform as a Service

PaaS provides the ability to develop, test, deploy, host, and maintain applications, enabling a web-based user interface that's supported by an architecture that can handle multiple concurrent users in development. PaaS has built-in scalability, load-balancing, and tools for billing and subscription management. An example of PaaS would be Salesforce.com, which provides a platform for managing, developing, and deploying applications related to contact management.

Infrastructure as a Service

IaaS generally provides broader distributed resources, dynamic scaling, and variable cost utility pricing. It also often allows multiple users on a single piece of hardware. Examples of IaaS include Amazon EC2, Windows Azure, and Rackspace.

The Marketing of Cloud Services

Do all these services sound vague, confusing, or arbitrary? Well, there's a lot of "bleeding" of functionality between these marketing classifications. The point is that these services are packaged for marketing to IT customers. There are no hard and fast rules about what truly separates one type of service from another. It's more a matter of the degree by which various services are packaged and the prices that providers can charge for each.

Perhaps the easiest way to envision how all these pieces within cloud computing fit together is to build a conceptual pyramid of services with SaaS in the top tier, PaaS in the middle tier, and IaaS in the supporting base tier (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Current Models in the Cloud

But it's also wise to remember two things: First, "cloud" is a marketing structure based on what providers are offering today. Second, cloud service architectures are still rapidly developing, and it's likely there will be new categories of services that are delivered in the future. These may include intelligent infrastructural device management services—such as electrical grid or factory air conditioning control—sold as services to organizations that do not want the burden of maintaining their basic factory infrastructures. So, as individual devices (sensors, controls, etc.) become more intelligent and connected through the IP (the "Internet of Things" idea), there will invariably be future ways for the services that monitor and control those device to be packaged and sold into the cloud market place. For instance, imagine your manufacturing company develops the idea for a new product. Design can be outsourced through the cloud, and all the financial, marketing, sales, and distribution software can be delivered as SaaS or PaaS.

But what if an entire manufacturing facility itself could be delivered as a service through the cloud too? This would be a service of greater breadth than a supply chain software package. In essence, it could be the kind of service that Apple uses today in its manufacturing of the iPhone using Foxconn in

The point is that cloud services are growing, will change, and reflect the ambitions of entrepreneurs to market their expertise in a metered, service-level model.

The Economics of IT

So, with this understanding of what's in (or may one day be in) the cloud, how is IT to understand and compare the economics of cloud versus in-house?

Traditional in-house architectures are composed of hardware, software, and network infrastructures: IT buys the computers, printers, and sundry devices that the company wants to use. It builds or licenses software—operating systems, applications, etc. —that contain the business logic services the company wants to utilize. It connects those devices to its network, configuring protocols devised by engineers, and then trains users in how to utilize the systems. IT then maintains this infrastructure with upgrades, patches, and training services that, over time, represent the in-house architecture that has propelled businesses for years.

Financially, depending on how a company's general ledger is set up, part of the economics of in-house are represented as direct expense—such as capital expense for equipment—and part is represented as indirect expense—such as heating and cooling of the facilities, labor, training, etc. Every company's CFO looks at these IT expenses and tries to align the value of the services with the company's bottom line. In that effort, any opportunity to reduce those expenses, while still providing or expanding the services needed by the company, is considered a win-win scenario.

So how do you compare the economics of cloud services to in-house IT?

The Intangible Economics of IT

If the target is simply to make a new application available to the organization, IT already has the traditional tools to quantify the costs of equipment, license fees, consulting fees for customization, and ongoing maintenance fees to compare implementing the application in-house to a similar SaaS offering in the cloud.

But there are intangibles offered by an in-house IT staff that are more difficult to quantify and compare.

A good example might be implementing an email server in a SaaS environment versus buying the equipment, purchasing the software licenses, and calculating the ongoing costs of managing the system. Any CIO or CFO can tally up the direct costs of purchase and licensing fees, readily identify the indirect costs of in-house IT, and then compare those costs to the costs promised by the SaaS version of the same service.

However, only experience with a particular provider of the SaaS application will answer the question of the intangible values of good service. Performance, for instance: If sub-second response time is a requirement of the email application, how can IT quantify that value to the company's bottom line? What about application support? If on-the-spot technical response to problems is the criteria by which the IT service is to be measured, one can only calculate the value of a similar SaaS implementation when there's a disruption requiring a response.

Delivering Fast Solutions from the Cloud

For these and other reasons, SaaS may be a great opportunity when bringing in a new application to the organization, or replacing an obsolete or aging version of an existing application. If service expectations are low or undefined, there's a pretty good chance that the return on investment will be high. Costs are definable and mostly controllable based upon usage factors. The indirect costs associated with IT are greatly minimized, and there is no capital investment for extra equipment.

The Economics of Migrating to Cloud

But when it comes to migrating an existing application (a highly customized software package or a custom-built in-house application) to the cloud, the economic factors and variables can become highly complex and require substantial analysis.

The Department of Computer Science and Engineering at the

What they found is that the cost of migrating existing applications to the cloud—with the prerequisites of altering the code, provisioning the services, performing the migration, doing the testing, and then deploying the applications—is not trivial. According to their analysis, "application characteristics such as workload intensity, growth rate, storage capacity and software licensing costs produce complex combined effect on overall costs." Their analysis reveals that…

- A complete migration of an application is cost-effective only for "small/stagnant businesses/organizations."

- The cost of migration for larger, more dynamic organizations is—for custom or home-built applications—too great, because many variables can overwhelm the longer-term cost savings that might be returned.

Hybrid In-house/Cloud Scenarios

The authors' findings are based upon two opposing hybrid implementation architectures: vertical partitioning of an application, in which part remains in-house and part is in the cloud, and horizontal partitioning, in which the entire application exists both in-house and in the cloud.

In their vertical partitioning scenario—in which a database server resides in the cloud and an application server resides in-house—the overall expense of data transfer between application and server becomes too expensive to maintain appropriate throughput and response times. Increasing the performance on either end is still dependent upon the network pipe, and guaranteeing that that network pipe can deliver at an appropriate performance level becomes very costly quickly.

By comparison, the study found that vertically partitioning an application—in which both the application and its database are replicated between the cloud and an in-house server—offers a means of expanding the access to the application, for periods of high use, at a reasonable expense.

The Evolving Economics of Cloud

The

Which is more economically viable? In-house IT or cloud? How does one decide? Common sense and a little number crunching can solve the immediate question at face value. But beware the ideologue or marketer who tries to sell you on wholesale cloud migration. Their heads may be in the cloud, but their hands are undeniably aimed for your purse.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new. IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online