For those of us who come from a technology background, it is tempting to believe that the purchase of a knowledge management (KM) system will solve the problems our organizations face by capturing the knowledge from our best and brightest employees. After all, if a computer that's coupled with a database and connected to the Internet cannot capture information, retain it, and enable rapid retrieval, what can? This is the message we hear from the purveyors of KM solutions.

Though selecting the appropriate software is just as important for implementing KM within an organization as it is for any other project, there is far more to a successful KM initiative than what happens within the IT department. Before software selection is even considered, certain areas of the business must be evaluated. The successful execution of a KM initiative requires support from the CEO and the rest of the C-level executives.

If your organization decides to embark upon a KM initiative, there are a few things you need to know so that you are not caught off guard when the project is launched. You need to know what knowledge is, how it is captured, what interferes with the sharing of knowledge, how knowledge is shared, and how it can be maintained.

What Is Knowledge?

When we begin to have serious discussions about knowledge, we need to ensure that we understand what is meant by "knowledge." Knowledge is broken down into two categories: explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge is knowledge that is easily observed, easily explained. Tacit knowledge is not easily observed, not easily explained. Tacit knowledge may be known so well that it becomes invisible to us. As an example, it is easy to explain that one must start a car before it can be driven. In fact, most children realize this before there is any effort to teach them to drive. They have learned the basics of driving by observation. This is explicit knowledge.

The same child who can, as my five-year-old daughter does, explain the basics with absolute confidence is at the same time completely unaware of the minor adjustments we make as we drive a car. They are unaware because the tacit knowledge we have of driving in heavy traffic, on wet roads, in cold weather, and in the presence of an erratic driver is covert; it is unseen. This is tacit knowledge--that which we know but cannot easily explain to someone else. Experts in any field will often claim that they "just knew" what to do. What they mean is that, based upon their experiences--years of successes and failures--they were able to quickly determine the best course of action.

When discussing the need to capture knowledge, it is the tacit knowledge that is the Holy Grail. Tacit knowledge is what separates the expert from the novice. It is the tacit knowledge that the organization needs to capture.

Types of Knowledge

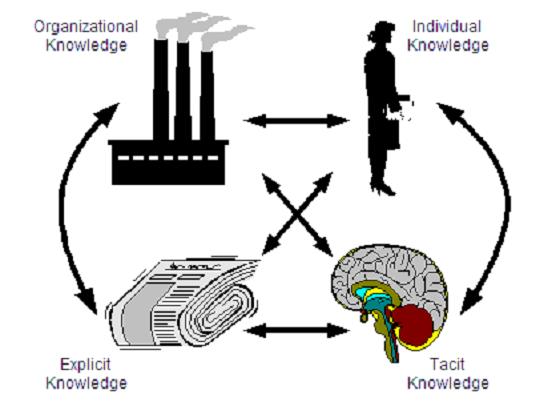

In his book on e-Learning, Marc Rosenberg introduces us to the concept of four types of knowledge: organizational, individual, explicit, and tacit. Figure 1 shows how they are related to each other. Knowledge, even when it is organizational or individual is still either explicit or tacit in nature.

Figure 1: Rosenberg explains the four types of knowledge and their interrelationships. (Click images to enlarge.)

Historically, organizations have only had access to individuals' knowledge while they worked at the organization. The tacit knowledge they had walked out the door when they left. This failure to have captured the tacit knowledge is often made clear when problems arise that can't be easily solved because the knowledge left the company.

Interaction of Knowledge

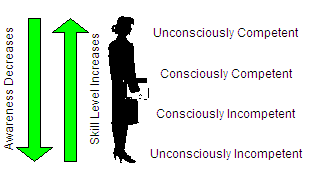

Consider what happens when we learn a new skill. When we first begin to learn, we are "unconsciously incompetent." We have no knowledge and are not even aware of what we would need to know to perform well. Once we begin to learn, we become "consciously incompetent." We are aware that we do not know and begin to realize what we will need to know to perform well. Once we have learned the skill and are performing it well, we are "consciously competent." We know what is expected of us, and we know we are performing well. Once we have been performing for a period of time and grow comfortable, we become "unconsciously competent." We are not aware of the steps we take to perform well; we just perform. Figure 2 shows this progression of skill as we move from having no experience to performing as an expert.

Figure 2: As individuals move from ineptitude to expert performance, they lose consciousness of what they know.

Those who perform at expert levels tend to be unconsciously competent. Thus, when asked what they do that causes them to perform better than others, that blank stare is real. They don't know. Wayne Gretzky was once asked what made him such a great hockey player. His response was, "I skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it is." Sounds simple, but how did he know where the puck was going to be? I would surmise that he had a mental game going on while he played the real game. His mental game was one of "what if?" and it was the outcome of his mental game that allowed him to predict where the puck would be in the real game. This is not something easily explained to an inexperienced player.

In Gretzky's case, it was the interaction of the real game he was playing with the stored memory of all the games he had ever played, coupled with his knowledge of the opposing players, that allowed him to perform his amazing predictions on ice. Putting this into Rosenberg's view of tacit knowledge, Gretzky had to know the organizational behavior of his team and that of the opposing team. He knew how he performed and how the other individuals (the teams) would perform. You can see the complexity of the interaction of knowledge, and this is only describing the performance of a single individual.

Capturing Knowledge

Tacit knowledge needs to be codified so that knowledge is captured from the best and brightest employees. Yet tacit knowledge can be so embedded in how experts think that they are not even aware of what they know. In fact, some research even suggests that when experts are asked to explain how they do what they do, they leave out steps. As I said previously, they become unconsciously competent. How then can tacit knowledge be captured? Here are some methods that work well.

After-Action Reviews

A great way to capture knowledge is to debrief the key players as soon as a project is completed. It does not matter if it was a success or failure; you want to capture what happened and what can be done differently next time. The after-action review should not be an onerous process. It should just be a review of what was done, what work products (see below) that were created could be used again, what could be changed in the proposal and contract the next time a similar project is undertaken, and so forth. In short, review the project, looking for anything that will improve operations.

Apprenticeship

This is a return to the methods of old. Think of the ancient guilds with the secret initiation rituals. Here, a person is assigned to work with the subject matter expert (master) for a prolonged period of time. This provides the opportunity for the apprentice to learn by doing.

Center of Competency

By creating a central location for storing knowledge, the company creates a single place to find answers and seek out the wisdom of the experts. These are known as Centers of Competency or Communities of Practice.

Coaching and Mentoring

Though coaching and mentoring are different programs, I have combined them here for simplicity's sake. Both coaching and mentoring seek the same result: improved performance. It is the methods they employ that differ. When employees work with a coach or mentor, they are able to improve faster than if left to their own devices.

Embedded Knowledge

By working with subject matter experts, a team of knowledge engineers can work out a set of rules or heuristics that can be programmed into a decision support system. A common example would be the knowledge of the loan officer who has the lowest rate of defaults. The hidden factors she senses would be uncovered and used to develop a system that allows faster and better loan funding choices throughout the organization.

Knowledge Inventory

There are times when just knowing who to go to is invaluable. By using email filtering software, peer nominations, self-identification, or other methods, a company can learn which employees are the "go-to" people when others need answers. The ability to get an answer fast is what this allows an organization to do.

At IBM, we used experimental software to broadcast a message worldwide to known experts. Within a firm the size of IBM, it is not unreasonable to think that there must be someone available 24x7 who could answer a question. The challenge is in knowing to whom to send such a request for help. This software was designed to identify who was online within an "expert group" and then send them the request.

Stories

We all love a good story. All of us have stories that we heard that stick with us. The ability to motivate through a narrative is a timeless technique of passing knowledge on to others. Recently, there has been a tremendous interest in reviving this form of training. Learning to tell stories in the work place so that others learn and the story itself is captured is a technique that more organizations should look into.

Work Products

A fairly easy way to capture knowledge is to capture the work products of the best people for use by others in the organization. Work products can be proposals, letters, project plans, reports, or designs. They can be intermediate or final results of work. The goal is to stop reinventing the wheel and leverage the work that others have done.

Knowledge Interference

It would be disastrous to assume that a KM system will be used just because it exists. Problems tend to arise that need to be dealt with. Those problems are a result of the way in which a company rewards its people.

Many companies have incentive programs to reward employees who excel at performing in the way the organization wants them to. To ensure a successful KM initiative, the organization needs to ensure it is rewarding the right behavior. To pass over for promotion employees who attended a conference to gain new skill will not encourage others to gain new skills. Employees who are reprimanded for teaching how to solve a problem instead of just solving it quickly will not likely want to share expertise again.

What of the employees who hoard knowledge and force everyone to come to them? Most of us have seen such employees be rewarded because upper management sees that everyone depends on them. Management loses sight of the fact that this situation has arisen slowly over time because "key" employees won't share knowledge, seeing this as a form of job security. After all, "If I'm the only one with this knowledge, how can they ever get rid of me?" This is misguided thinking in the knowledge organization.

What this thinking creates is a culture of hoarding knowledge, not offering help until it is requested and is advantageous to do so. It creates the very opposite of the learning organization. Management needs to ensure that employees are rewarded for openly sharing what they know and striving to gain new knowledge so that they can contribute more to the organization. Management needs to take a hard look at their practices and make sure they reward the correct behavior. After all, we tend to perform as we are measured.

One last point, and this one is very important: A company that is working hard to create an open environment where employees openly help each other, share what they know, and willingly contribute to the knowledge of the organization can destroy all the hard work if they lose sight of what they are doing. The instant the company lays off experts because they are no longer needed (due to their willingness to share the tacit knowledge), the KM initiative is dead. Employees will see that knowledge is key and that once the organization pulls all it wants from the experts, it will discard them. Not a single employee will contribute any more knowledge freely. And the failure to have a free exchange of knowledge will doom even the best KM initiative.

KM initiatives only work when there is a strong trust within the organization. If that trust is not there, the organization might be better off building a trusting environment and not working on a KM initiative. Once the trust is there, the KM initiative can be started.

Knowledge Maintenance

One of the issues we had at IBM was the volume of knowledge that we captured. After working for years to build systems that allowed sharing knowledge, storing work products, and locating experts, we had too much information. I once looked for an expert only to find that of the 200+ names I found in the system, all but 11 had left the company or had transferred into areas that put their expertise in question. The amount of time I spent in cross-referencing the list of experts against the internal global directory was eye-opening. We had developed a system that accepted information but had no way of archiving or purging knowledge that was out-of-date.

An organization needs to ensure that there is a process in place to remove obsolete information from the knowledge repository. For the knowledge creation business, this is critical. As teams use the knowledge of the company, as they strive to build upon what is known, they need to be working with the latest thinking.

KM Is More Than Technology

KM is much more than a software package. It is a business discipline that goes far beyond the IT department. Yet, without technology, the KM initiative will fail.

Careful planning must be done to ensure the organization is ready to embrace and support the KM initiative. A review of reward and incentive programs is required. A hard look at how managers reinforce behavior must be conducted, and those in leadership positions must model the correct behavior.

All employees need to be convinced that embracing KM is important and that they will benefit from using and sharing knowledge. They must be encouraged to share their knowledge.

KM is more than technology, but without technology, it would not even be feasible. So the next time management suggests implementing a KM system to solve problems, hold up a mirror and ask them, "Can you first change the behavior of these? KM must start at the top if it is to succeed!"

David Hildebrandt is the founding member of iDREIA, a firm providing organizational assessment and design of knowledge and learning management systems worldwide. David is also a faculty member of the University of Phoenix. He can be reached by email at

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn:

IT managers hoping to find new IBM i talent are discovering that the pool of experienced RPG programmers and operators or administrators with intimate knowledge of the operating system and the applications that run on it is small. This begs the question: How will you manage the platform that supports such a big part of your business? This guide offers strategies and software suggestions to help you plan IT staffing and resources and smooth the transition after your AS/400 talent retires. Read on to learn: Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

Business users want new applications now. Market and regulatory pressures require faster application updates and delivery into production. Your IBM i developers may be approaching retirement, and you see no sure way to fill their positions with experienced developers. In addition, you may be caught between maintaining your existing applications and the uncertainty of moving to something new.

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online